No princípio era o verbo. A frase que abre o primeiro capítulo do Evangelho de João e remete à criação do mundo, assim como também faz o Gênesis, é a mais famosa da Bíblia. A ideia de que o mundo é criado pela palavra, porém, é tão estruturante que está presente em outras religiões, para muito além das fundadas no cristianismo. Como humanos, a linguagem é o mundo que habitamos. Basta tentar imaginar um mundo em que não podemos usar palavras para dizer de nós e dos outros para compreender o que isso significa. Ou um mundo em que aquilo que você diz não é entendido pelo outro, e o que o outro diz não é entendido por você, para alcançar o que é ser reduzido a sons porque as palavras perderam seu significado e, portanto, se tornaram fantasmagorias. Quando uso a palavra “dizer” não significa apenas falar, porque a gente se diz com palavras, de várias maneiras para além da fala. Mais ainda do que o mundo que habitamos, a palavra é o que nos tece. Aquilo que chamamos mundo é uma trama de palavras.

O que acontece então quando a palavra é destruída e, com ela, a linguagem?

Essa é a experiência do bolsonarismo, nome dado no Brasil a um fenômeno que se dissemina no planeta, ganhando em outros países nomes de outros déspotas. Os personagens que emprestam nomes locais ao fenômeno são importantes e, em cada país, há particularidades. Mas o fenômeno precede aqueles que o encarnam e, infelizmente, irá além deles. É neste contexto que busco interpretar o Nobel da Paz dado a dois jornalistas que lutam pela busca da verdade contra ditadores eleitos que têm na destruição da palavra seu principal meio para alcançar e se perpetuar no poder.

A filipina Maria Ressa está proibida de sair de seu país, já foi presa duas vezes e pagou fiança outras sete por combater com jornalismo o governo de Rodrigo Duterte. Ela é editora do site de reportagem investigativa Rappler. O russo Dmitri Muratov dirige o jornal Novaia Gazeta, que ousa confrontar com fatos o regime de Vladimir Putin. Desde 2001, seis repórteres do jornal foram assassinados. A escolha de dar o Nobel a esses dois jornalistas que são símbolos da resistência contra a opressão em seus países é uma declaração da importância da imprensa para a democracia. O Nobel, prêmio que destaca aqueles que colaboraram para o bem comum, representa o conceito de humanidade consolidado ao longo do século 20. Como bem comum e democracia se tornaram uma espécie de irmãos siameses no mundo do pós-guerra, um prêmio a jornalistas no Nobel da Paz faz todo sentido. Mas em que momento chega esse prêmio à imprensa, na conturbada terceira década do século 21?

A justiça da premiação a esses dois jornalistas é inegável. A escolha de valorizar a imprensa como pilar da democracia e, assim, valorizar a busca das verdades, assim mesmo no plural, e a importância dos fatos, num momento em que um e outro estão corroídos, também. A questão é: quem escuta?

Se jornalistas são atacados e desqualificados, se outros são presos e outros ainda executados é porque a imprensa ainda tem impacto sobre a sociedade. Suspeito, porém, que estamos chegando, pelo menos no Brasil, a um momento ainda mais grave. Para uma parte da população, a imprensa já não importa em nada. Todas as iniciativas de expor a mentira das chamadas fake news, entre elas as agências de checagem, são muito importantes. Mas são muito importantes apenas —ou pelo menos principalmente— para aqueles que respeitam os fatos e já sabem que aquelas notícias são falsas. Para todos os outros, já houve uma decisão prévia de que tudo o que a imprensa publica é falso. Esta é a razão pela qual em golpes como o de Jair Bolsonaro não é necessário censura, como aconteceu em ditaduras passadas, já que para essa parcela da população nada que seja estampado nas manchetes dos jornais vai colar.

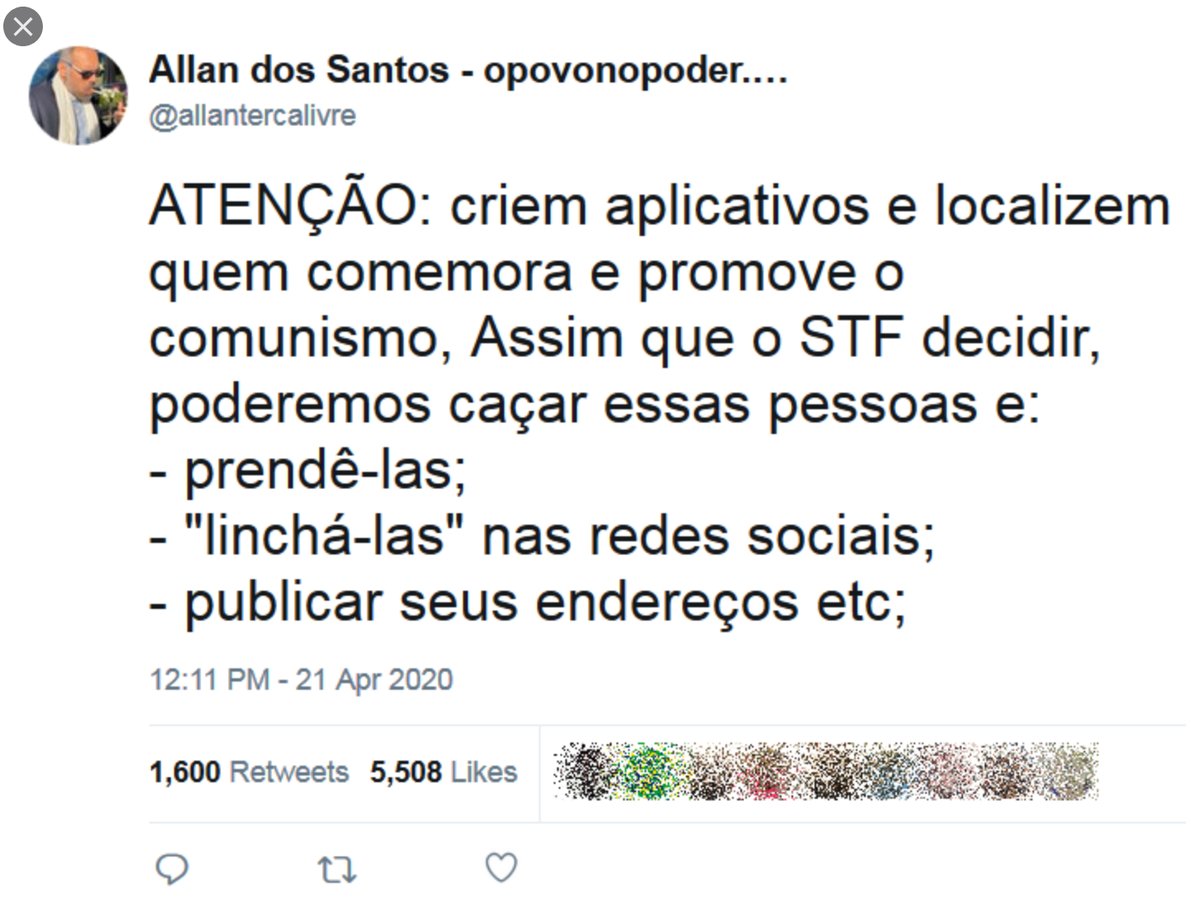

Isso não significa que os jornalistas deixarão de correr riscos. Como o governo Bolsonaro mostrou, os ataques são necessários para manter o apartheid político ativo. Se forem contra jornalistas mulheres, melhor ainda, na medida em que a misoginia e o machismo rendem votos para Bolsonaro. É importante que a base de seguidores seja mantida em estado de ódio constante e seja lembrada, também de forma constante, que a imprensa “só diz mentiras”. A estratégia torna mais fácil fabricar “fatos alternativos” como se verdade fossem. “Fatos alternativos” são impossibilidades lógicas. São também mentiras facilmente desmontáveis, como as agências de checagem demonstram toda vez. Mas, se uma parte da população não lê nem vê nem escuta, de que adianta?

O que está em jogo é algo mais profundo: uma mudança na forma de apreensão da realidade, que confronta os pilares que forjaram a imprensa e o funcionamento da sociedade moderna. Por uma série de razões, o verbo que progressivamente passou a mediar uma parcela significativa das pessoas na sua relação com a realidade é “acreditar”. Não mais os verbos iluministas do duvidar, investigar, testar, confrontar, comparar etc. Mas acreditar. É uma mediação religiosa da realidade, determinada pela fé. A crença se antecipa aos fatos, e assim os fatos já não importam. É como se as pessoas passassem a ler a realidade da mesma forma que leem a Bíblia. Esta é a razão que determina a crise da imprensa, da ciência e de outros fundamentos que constituíram a modernidade, baseados na investigação e no questionamento constante, para os quais a dúvida é que move o processo de apreensão da realidade e de construção do conhecimento sobre o mundo.

É claro que essa mudança tem relação com o crescimento de um determinado tipo de religião, no Brasil marcadamente a expansão do neopentecostalismo de mercado, através de denominações religiosas produzidas por essa fase ainda mais predatória do capitalismo. Na minha interpretação, porém, a mediação da realidade pela fé é (não só, mas) principalmente sintoma da transfiguração do planeta pela crise climática. Ainda que a maioria das pessoas não seja capaz de nomear os impactos dessa monumental mudança em suas vidas, todos estão sentindo que o mundo que conhecem se desfaz debaixo dos pés. Mesmo para aqueles que a vida cotidiana sempre foi muito dura, a dureza desconhecida é ainda mais brutal do que a conhecida. No desamparo, em que também as instituições se desfazem, resta crer. E resta crer mesmo para aqueles não religiosos, no sentido estrito. E resta crer não apenas numa religião, mas em uma realidade que, se não é real no sentido de corresponder aos fatos, se torna real para quem nela acredita. Nesta proposição, a mediação da realidade pela crença seria uma adaptação à emergência climática que, em vez de enfrentá-la, a agrava.

Como já escrevi mais de uma vez, os ditadores eleitos que alcançaram o poder pelo voto a partir da segunda década do século são vendedores de passados que nunca existiram porque não têm futuro para oferecer, já que as forças que representam são as principais responsáveis pela alteração do clima e da morfologia do planeta. No caso de Jair Bolsonaro, principalmente os setores do agronegócio predatório e da mineração. A aliança alcançada no bolsonarismo entre agronegócio, mineração, corporações transnacionais de agrotóxicos e produtos ultraprocessados e grandes pastores do neopentecostalismo de mercado não é um acaso. Em comum, essas forças buscam seguir avançando sobre a natureza e lucrando num momento em que são confrontadas pela corrosão do planeta. No Brasil, especialmente pela destruição da Amazônia, que pode chegar ao ponto de não retorno nos próximos anos. Mas também a destruição persistente de outros biomas e de seus povos, como o Cerrado e o Pantanal.

Só a mediação da realidade pela crença pode garantir a continuidade da exploração e do lucro pelas grandes corporações capitalistas num momento em que o planeta superaquece devido a suas ações. É por isso que parte dos executivos de corporações transnacionais toleram a companhia pouco refinada dos pastores de mercado e principalmente de uma criatura tosca como Jair Messias Bolsonaro, que tem levado a crença como ativo político ao paroxismo. A palavra “seguidores”, tomada emprestada das seitas e religiões pelas redes sociais, tornou-se sinalizadora de um fenômeno na política em que mesmo os ateus se comportam como crentes. Pela tomada da política pela mediação religiosa, ironicamente a mais famosa frase bíblica foi traída. No princípio era o verbo. Mas então o verbo passa a ser sistematicamente destruído como projeto de poder.

Nessa fase, portanto, ainda é necessário bater na imprensa e trabalhar para a desqualificação de jornalistas. Talvez numa segunda fase já não será mais preciso, na medida em que a imprensa poderá seguir importante, mas apenas para uma bolha, e com dificuldades cada vez maiores para penetrar em universos além dela. Este é hoje o grande desafio do jornalismo e do mundo que produziu a imprensa como a conhecemos.

As próximas eleições quase certamente ampliarão o fosso no mundo dos humanos. A ótima reportagem sobre o avanço do Telegram entre a extrema direita global, publicada no jornal O Globo, aponta a estratégia em acelerada execução. Sem representação legal no país nem moderação de conteúdo, o Telegram não respondeu às tentativas de contato da Justiça brasileira. Com grupos para até 200 mil pessoas e canais com capacidade ilimitada de inscritos, o Telegram é o mundo perfeito para a propaganda em massa sem a necessidade de atender à legislação dos países. Subverte, em nome da “liberdade de expressão”, o próprio conceito de liberdade de expressão, em que limites precisam ser respeitados para que o crime não se imponha. No Telegram, por exemplo, circulam livremente vídeos com pornografia infantil, assim como armas são comercializadas sem nenhuma normatização e fiscalização.

A partir das denúncias do uso ilegal do WhatsApp na campanha de Bolsonaro, em 2018, o aplicativo de mensagens de Mark Zuckerberg tomou algumas medidas para impedir ou pelo menos controlar minimamente a disseminação de fake news para uso eleitoral. Como alternativa para a eleição de 2022, Bolsonaro passou a apostar então no Telegram: na semana passada, seu canal no aplicativo bateu a marca de 1 milhão de seguidores. Fundado em 2013 na Rússia pelos irmão Nikolai e Pavel Durov, com sede em Dubai, nos últimos anos o Telegram teria mudado de jurisdição várias vezes para escapar de qualquer regulação. Os auxiliares de Bolsonaro hoje trabalham arduamente para construir na plataforma uma base de crentes políticos capazes de levá-lo à reeleição. Donald Trump, por sua vez, depois da criminosa invasão do Capitólio, foi banido das redes sociais Twitter e Facebook, por meio das quais propagava suas mentiras e insuflava seus seguidores. Seu ex-conselheiro, Jason Miller, lançou então neste ano uma nova rede social, a Gettr. Em setembro, Miller foi recebido por Bolsonaro no Palácio do Alvorada.

É na internet que está sendo forjada uma realidade sem lastro nos fatos. Neste ato em processo, os pilares do mundo que conhecíamos são corroídos. Entre eles, a imprensa, a ciência e a democracia. É importante fazer a ressalva de que obviamente não vivíamos num mundo maravilhoso que foi corrompido por homens do mal. A democracia nunca chegou para todos. É notório que grande parte da população brasileira viveu na arbitrariedade das forças policiais mesmo após a redemocratização do país e também sem acesso a direitos básicos. O mesmo vale para outros países, inclusive para as parcelas pobres de países considerados ricos, como o brutalmente desigual Estados Unidos.

No Brasil, a imprensa —branca, majoritariamente liberal, liderada preferencialmente por homens e com posições ocupadas pelos filhos da classe média que puderam chegar à universidade e, mais recentemente, aos MBAs nos Estados Unidos e na Europa— nunca representou a diversidade da sociedade brasileira, deixando largas camadas fora dela e dando diferentes valores à vida humana. Basta ver o espaço dado à morte dos ricos (e brancos) e à dos pobres (e pretos), à vida dos ricos (e brancos) e à dos pobres (e pretos). Só recentemente, por pressão externa, a imprensa tem aberto espaço aos negros, maioria da população, e começado a se abrir para a diversidade de gênero. Vale dizer ainda que, disposta a defender seus lucros e interesses, no Brasil as principais famílias que dominam a mídia impediram o avanço do debate da regulamentação da imprensa como se fosse um atentado à liberdade de expressão e, assim, uma grande parte das concessões públicas de TV é usada (e abusada) pela mais nefasta doutrinação religiosa disseminadora de teorias conspiratórias e anticientíficas.

A ciência tampouco escapa de um olhar crítico. É responsável direta pela emergência climática, processo de alteração do clima e da morfologia do planeta iniciado na Revolução Industrial e acelerado no século 20. Sem contar que fez muitas promessas que não foi capaz de cumprir —e ainda faz. Em países como o Brasil, em que a educação é uma tragédia jamais enfrentada com o investimento necessário, a maior parte da população não é capaz de compreender a ciência que impacta a sua vida e jamais houve preocupação suficiente de seus agentes para mudar esse estado geral de ignorância por falta de acesso à informação científica inteligível.

Isso não significa, porém, que a democracia, a imprensa e a ciência sejam menos do que essenciais para a criação de um futuro em que possamos viver. Com todas as suas falhas, omissões e exclusões, esses três pilares conectados são parte do melhor que a humanidade produziu. É (também) com muita ciência, obrigatoriamente contando com o conhecimento ancestral de povos-natureza, como os indígenas, que temos alguma chance de enfrentar o superaquecimento global e a monumental perda de biodiversidade. É também dentro da própria imprensa que têm surgido as melhores críticas à imprensa. A melhor forma de enfrentar os problemas da imprensa é com jornalismo da melhor qualidade, feito com rigor e honestidade. Ampliar a democracia é também o melhor caminho disponível para enfrentar sua crise. E, num momento de ecocídios em curso, é preciso ampliá-la também para outras espécies.

Durante séculos, em diferentes sociedades e línguas, é importante lembrar, a linguagem serviu —e ainda serve— para manter privilégios de grupos de poder e deixar todos os outros de fora. Quem entende linguagem de advogados, juízes e promotores, linguagem de médicos, linguagem de burocratas, linguagem de cientistas? A maior parte da população foi submetida à violência de propositalmente ser impedida de compreender a linguagem daqueles que determinam seus destinos. E então surgem criaturas como Jair Bolsonaro e outros que falam na língua que são capazes de entender. E mentem na língua que entendem. E dizem que é ótimo não entender nada sobre quase tudo. Parte da população decide, como reação, dar a pior resposta à sua exclusão fazendo e exercendo a exaltação da ignorância. Criam sua própria bolha de linguagem e passam a excluir todos os outros. É estúpido, mas é uma reação. Afinal, por séculos poucos se importaram que grandes parcelas das populações do planeta ficassem de fora da linguagem em que suas vidas eram decididas.

Ressalvas feitas, o momento é brutal. É na brutalidade do que vivemos que o Nobel da Paz dado a dois jornalistas pode ser interpretado como o grito desesperado de quem assiste a pilares como a imprensa desabarem. Não porque a imprensa deixará de existir, mas porque poderá ter impacto apenas sobre uma parte da população —o que é diferente do passado recente, em que também era feita e controlada por uma minoria, mas tinha impacto sobre o conjunto da sociedade. Trata-se em parte de uma reorganização dos espaços de poder, mas feita da pior maneira possível e, em grande medida, falsa, já que corrói a possibilidade de qualquer transformação real. Ao final, os principais beneficiados são minoritários e os mesmos de sempre, razão pela qual Bolsonaro continua no poder apesar de todos os seus crimes. Em um mundo em transtorno climático, as grandes corporações decidiram sacrificar parte de seus aliados históricos para manter um sistema que colocou a espécie diante da possibilidade de extinção.

Esse é o abismo do qual nos aproximamos. Estamos à beira de algo com a magnitude do rompimento da linguagem que une os humanos, para além das diferenças de língua: uma parcela da população global aderindo a uma realidade falsificada, mas que, pela adesão, passa a se tornar real. Tudo indica que as eleições de 2022, no Brasil, serão o laboratório de ensaio dessa nova fase da crise da palavra, para muito além do que se entende por polarização. Ao romper a linguagem com a qual é possível se encontrar, aquela que compartilha de uma base de significados de consenso baseado em evidências, sejam elas objetivas ou subjetivas, estamos diante de um fenômeno inédito. Num planeta em colapso climático, em que mais do que nunca é necessária uma linguagem comum para determinar o comum pelo qual lutar, a humanidade parece se dividir em duas gigantescas bolhas impermeáveis uma a outra.

Lutar pelo futuro é lutar no presente para que as palavras voltem a

encarnar, permitindo uma linguagem comum. Não como antes, mas uma em que

realmente caibam todas as gentes e suas diferenças, tornando o debate

das ideias possível para a criação de conhecimento e de ação baseada em

conhecimento. O que tínhamos não era justo e nos trouxe até esse momento

limite. Para seguirmos existindo, teremos que ser melhores do que fomos

e criar uma sociedade capaz de viver em paz

com todas as forças de vida do planeta. Se o princípio é o verbo, o fim

pode ser o silenciamento. Mesmo que ele seja cheio de gritos entre

aqueles que já não têm linguagem comum para compreender uns aos outros.