"Quem gosta de Covas é de-

funto. O povo gosta é do

Boulos”, repete, aos bra-

dos, um histriônico apoia-

dor do candidato do PSOL

à prefeitura de São Paulo,

em frente a uma padaria

na Estrada do M’Boi Mi-

rim, via estrutural de 16

quilômetros de extensão

que liga o Jardim Ângela ao Jardim São

Luís, na divisa com o município de Ita-

pecerica da Serra. Na chuvosa manhã da

terça-feira 17, dezenas de militantes es-

premem-se na calçada à espera do Celti-

nha 2010 prata, o “veículo oficial do novo

prefeito”, como define um risonho profes-

sor presente no ato, sem deixar de sacudir

a bandeira da campanha por um segundo.

A algazarra só é interrompida após o

anfitrião da festa desembarcar do carro

popular e tomar o microfone. “Não dá pa-

ra aceitar que a cidade mais rica do Brasil

tenha gente, como eu vi agora no trajeto

para cá, revirando lixo à procura de co-

mida”, discursa. “Isso vai mudar. A par-

tir de janeiro, vai ter renda solidária para

quem precisa, vai ter frentes de trabalho

nas subprefeituras. Vamos inverter prio-

ridades. A periferia vai ser ouvida e es-

tará no centro do orçamento da cidade.”

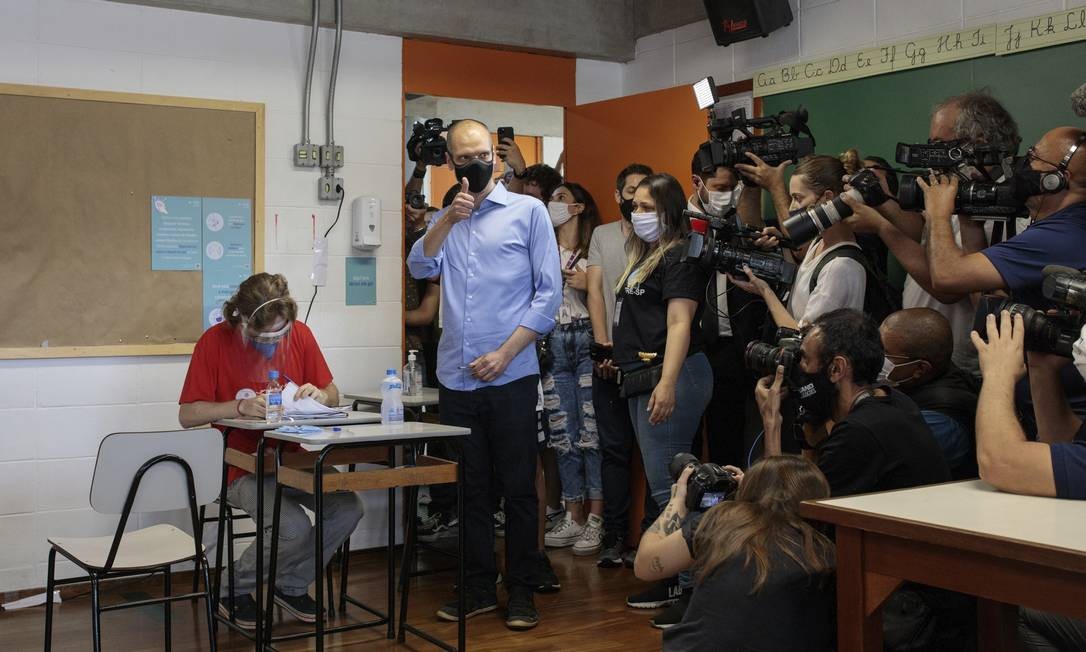

Após conquistar mais de 1 milhão de

votos no domingo 15, Guilherme Bou-

los, de 38 anos, fazia o seu primeiro ato

de campanha nas ruas do segundo turno.

A escolha do local não foi aleatória. Em

uma das regiões mais populosas da capital

paulista, ele prometeu duplicar a avenida

e instalar um corredor de ônibus exclusi-

vo, de ponta a ponta. “O custo é de 450 mi-

lhões de reais, existe projeto aprovado, as-

sim como tem projeto aprovado de esten-

der o metrô do Capão Redondo para o Jar-

dim Ângela, mas o PSDB nunca tirou do

papel”, afirma. “Para fazer isso, basta re-

ver as prioridades. A prefeitura gastou 100

milhões de reais numa reforma desneces-

sária no Vale do Anhangabaú, está gastan-

do outros 250 milhões de reais para reme-

xer em calçadas do Centro. Por que não

investiu esse dinheiro na M’Boi Mirim?

Aqui, passa gente do Fundão, do Jardim

Aracati, do Vera Cruz, do Horizonte Azul,

do Capela, um pessoal que demora até três

horas para chegar ao trabalho em ônibus

lotados. É desumano.”

Boulos aposta todas as fichas no voto

da periferia para virar o jogo em São Pau-

lo. Às vésperas do primeiro turno, o can-

didato despontava na segunda colocação,

mas aparecia tecnicamente empatado

com o ex-governador Márcio França, do

PSB, e o deputado federal Celso Russo-

manno, do Republicanos, partido nascido

das costelas da Igreja Universal do Reino

de Deus. Com apenas 17 segundos no pro-

grama eleitoral gratuito, o coordenador

do Movimento dos Trabalhadores Sem

Teto atropelou os rivais na reta final. Ter-

minou a disputa com 20,24%, bem à fren-

te de França (13,64%) e com quase o do-

bro do porcentual obtido por Russoman-

no (10,5%), que liderava a corrida eleitoral

até Jair Bolsonaro, seu cabo eleitoral, “sa-

botar” a campanha. Além da constrange-

dora derrota imposta ao bolsonarismo,

Boulos conseguiu eleger seis vereadores

do PSOL, a terceira maior bancada da ci-

dade, atrás do PT e do PSDB.

]

“O resultado das urnas consagra Bou-

los como um grande líder do campo pro-

gressista”, avalia o cientista político Cláu-

dio Couto, professor da FGV de São Pau-

lo. “Nesse campo da esquerda, vejo um

entusiasmo com ele que talvez eu não

veja desde a primeira eleição do petista

Fernando Haddad. Mesmo não ganhan-

do a prefeitura, ele ganhou a eleição em

um certo sentido. Ele sai muito maior do

que entrou, assim como o PSOL.”

Nem por isso, Boulos se dá por satis-

feito com o desempenho obtido até aqui,

em uma pequena coligação com os nani-

cos PCB e UP, este último estreante nas

eleições. “Bruno Covas achou que iria

ganhar no primeiro turno, mas chegou

a 32%. Se a maioria quisesse a continui-

dade do projeto tucano, ele não teria me-

nos de um terço dos votos válidos na cida-

de”, afirma. Virar o jogo em São Paulo se-

rá, porém, uma tarefa complicada. Com

o apoio das máquinas municipal e esta-

dual, o candidato do PSDB venceu com

uma vantagem de mais de 673 mil votos,

liderando em todas as 58 zonas eleitorais

da cidade. Os melhores resultados foram

nos abastados bairros do Jardim Paulis-

ta, com 44,52% dos votos, e Indianópolis,

com 44,05%. O tucano também teve bom

desempenho em áreas periféricas, como

Capela do Socorro (33,15%), Cidade Ade-

mar (33,28%) e Rio Pequeno (33,54%).

Uma pesquisa Datafolha do fim

de outubro apontou, ainda, que

46% dos paulistanos conside-

ram a gestão do prefeito boa ou

ótima durante a pandemia do

coronavírus, ao passo que 18%

a classificaram como ruim ou péssima.

Claro que o tucano tem as suas fragilida-

des. Sem grandes realizações para apre-

sentar, Covas tenta a todo custo esconder

o padrinho João Doria, cuja gestão é con-

siderada ruim ou péssima por 49% dos

moradores da capital paulista. Não por

acaso, uma das estratégias da campanha

de Boulos é lembrar, sempre que possível,

que Covas só se tornou prefeito porque era

vice de Doria, e este abandonou a cidade

para disputar o governo estadual.

Uma conjunção de outros fatores ali-

menta as esperanças do campo progres-

sista. As sondagens eleitorais indicam

uma diferença menor que a projetada

antes de os paulistanos comparecerem

às urnas. De acordo com uma pesquisa

divulgada pelo Ibope na quarta-feira 18,

Covas iniciou o segundo turno com 58%

dos votos válidos, contra 42% de Boulos.

Além disso, 21% dos entrevistados res-

ponderam que ainda podem mudar o vo-

to. Ou seja, virar o jogo pode ser difícil,

mas não impossível.

Não por acaso, a tão sonhada frente

de esquerda materializou-se no segun-

do turno das eleições paulistanas. PT,

PCdoB, PDT e Rede anunciaram apoio a

Boulos. Somente o PSB ainda não havia

tomado a sua decisão até o fechamento

desta edição. “Esse apoio será fundamen-

tal para avançar sobre redutos de outros

partidos e manter a mobilização nas ruas,

até para o Boulos ter tempo de se prepa-

rar para os debates e gravar os programas

do horário eleitoral”, explica Juliano Me-

deiros, presidente do PSOL. Do outro la-

do, Covas só conseguiu angariar a adesão

de Russomanno, que terminou a dispu-

ta com menos votos que os conquistados

por ele mesmo em eleições anteriores.

Orlando Silva, do PCdoB, foi

um dos primeiros a unir-se

a Boulos. Mesmo contraria-

do com as pressões de inte-

grantes do próprio partido

para desistir da candidatura

no primeiro turno em favor do candidato

do PSOL, o petista Jilmar Tatto deixou o

ressentimento de lado e subiu no palan-

que com a dupla. “Não existe qualquer

mágoa nem nada do tipo. Ao contrário,

vamos entrar com tudo na campanha”,

tratou de esclarecer. Lula, Ciro Gomes

e o governador do Maranhão, Flávio Di-

no, devem marcar presença no programa

eleitoral, agora com uma divisão igualitá-

ria de tempo. “No primeiro turno, tínha-

mos apenas 17 segundos. Agora, teremos

10 minutos de tevê, quase um debate por

dia. Isso vai fazer com que a nossa men-

sagem chegue a todos”, anima-se Boulos.

Extremamente bem-sucedida no pri-

meiro turno, a estratégia nas redes so-

ciais seguirá a mesma. “Foi graças às

ações que desenvolvemos nessa área

que Boulos passou a liderar entre os

eleitores de 16 a 24 anos”, comenta Jo-

sué Rocha, coordenador da campanha

do PSOL. Para dialogar com os jovens,

Boulos chegou a participar de um reality

show de um dia, transmitido ao vivo pelo

YouTube, disputou partidas de Among

Us, popular jogo da internet, enquanto

respondia perguntas de seus oponentes,

e marcou presença no podcast Flow, que

atrai milhares de aficionados por video-

-games, uma turma não muito politizada

e pouco identificada com a esquerda.

Agora, um de seus mais aguerridos ca-

bos eleitorais é o youtuber Felipe Neto,

que tem mais de 40 milhões de inscri-

tos em seu canal. O jovem influenciador

chegou a bater boca com Covas pelas re-

des sociais e divulgar uma lista com 28

razões para não votar no atual prefeito.

As ações nas redes sociais não se res-

tringiram, porém, a esse público. Vídeos

curtos, mas muito bem elaborados, sua-

vizaram a imagem que o líder dos sem-

-teto tinha no imaginário de eleitores de

todas as idades. Em um deles, os pais de

Boulos, ambos infectologistas e profes-

sores da Faculdade de Medicina da USP,

contam a trajetória do filho, desde que ele

decidiu, aos 16 anos, abandonar o Colé-

gio Equipe, um dos mais tradicionais de

São Paulo, hoje com mensalidades supe-

riores a 2 mil reais, para matricular-se em

uma escola pública do bairro. Um mês de-

pois, o adolescente havia fundado um grê-

mio e liderado um motim dos estudantes

contra a obrigatoriedade do uso de uni-

forme. Tirou cópias do Estatuto da Crian-

ça e do Adolescente, que impede a proibi-

ção da entrada de alunos sem uniforme, e

seguiu com os colegas até a Delegacia Re-

gional de Ensino para protestar. Foi a sua

primeira mobilização vitoriosa.

Da escola pública, Boulos passou di-

reto para o curso de Filosofia da USP.

Depois fez especialização em Psicolo-

gia Clínica e mestrado em Psiquiatria.

Na sua tese, dissertou sobre os efeitos

da participação em movimentos so-

ciais na redução dos sintomas da depres-

são. Àquela altura, havia participado de

programas de alfabetização de jovens e

adultos e estava engajado na luta por mo-

radia popular. Ainda com 19 anos, saiu

da casa dos pais, no bairro de Pinheiros,

para viver com os sem-teto em um acam-

pamento em Osasco. “Foi uma opção de-

le para sentir na pele a dificuldade que

aquelas pessoas estavam sentindo”, co-

menta o pai, Marcos Boulos.

Não se tratava de uma mera aventura.

O jovem Boulos dedicou a vida à luta por

moradia popular. Foi na ocupação Chi-

co Mendes, em Taboão da Serra, que ele

conheceu a sua esposa, Natalia Szerme-

ta, em 2005. Recém-casados, eles chega-

ram a morar próximo do córrego Piraju-

çara, que costuma transbordar sob chu-

va intensa. Depois, mudaram-se para o

Campo Limpo, onde os pais dela vivem.

Até hoje, o casal mora no mesmo bairro

periférico, com as filhas Sofia e Laura,

de 10 e 9 anos. Com a “sensibilidade so-

cial” adquirida em duas décadas de atua-

ção no movimento sem-teto, o candidato

do PSOL acredita ser possível conquis-

tar os votos dos moradores da periferia.

“Os tucanos estão habituados a tratá-los

como números, como estatísticas. Eu os

conheço pelo nome, são meus vizinhos,

meus companheiros de luta.”

Logo após a apuração dos votos no pri-

meiro turno, Covas fez um discurso que

entregou, logo de partida, uma das suas

estratégias na etapa decisiva: associar

Boulos ao radicalismo, de forma a insu-

flar o sentimento antipetista que preva-

leceu nas eleições de quatro anos atrás. No

debate promovido pela CNN Brasil, o tu-

cano voltou a insistir na tese. “O radicalis-

mo ideológico sabe criticar, mas não sabe

salvar vidas”, disse o candidato ainda no

primeiro bloco, ao falar sobre a pandemia

do novo coronavírus. “Ontem, fiquei até

assustado quando vi o seu discurso após

a apuração. Discurso cheio de raiva”, rea-

giu o adversário do PSOL. “Não sei. Talvez

porque você achou que a eleição estava ga-

nha, ficou preocupado com o crescimen-

to que nós tivemos, e agiu dessa forma.”

Em entrevista à Folha de S.Paulo,

Covas observou que o PSOL de

Boulos tomou o espaço antes

ocupado pelo PT, mas não se di-

ferencia muito dele. “É a mesma

raiz, a mesma linha, a mesma

matriz ideológica. Eles têm uma atuação

conjunta”, afirmou, sem perder a opor-

tunidade de expor a falta de experiência

administrativa do concorrente. O psolis-

ta rebate: “Tenho 20 anos de atuação no

movimento sem-teto, o que me deu uma

sensibilidade social que ele não tem. Além

disso, está ao meu lado Luiza Erundina,

que foi a melhor prefeita que esta cidade

teve. Com todas as dificuldades, ela criou

políticas públicas que geram frutos até ho-

je. E, obviamente, eu não vou governar so-

zinho, estarei com os especialistas que

ajudaram a construir o meu programa”.

A campanha do PSOL pretende dar

um destaque cada vez maior a esses

profissionais, para mostrar quem esta-

rá ao lado de Boulos na administração.

Na propaganda da tevê, o médico sanita-

rista Gastão Wagner e as urbanistas Ra-

quel Rolnik e Ermínia Maricato são pre-

senças quase certas. “No primeiro tur-

no, fomos alvo de fake news e de ataques

do Russomanno por 15 dias seguidos.

Ainda assim, continuamos crescendo e

até mesmo a taxa de rejeição diminuiu”,

observa Rocha, da coordenação da cam-

panha. Na avaliação da vice Erundina,

não é muito difícil expor a “falácia” por

trás do discurso de Covas. “Quando as-

sumi a prefeitura, eu também não tinha

experiência administrativa, mas tinha

uma equipe de altíssimo padrão. Paulo

Freire na Educação, Paul Singer no Pla-

nejamento, Eduardo Jorge na Saúde,

Marilena Chauí na Cultura, Lúcio Gre-

gori nos Transportes, Paulo Sandroni

na Economia. Enfim, tínhamos um mi-

nistério dos sonhos, que nenhum outro

governo brasileiro teve”, orgulha-se. “E

Boulos, mesmo sem ter o poder da cane-

ta, conseguiu viabilizar a construção de

23 mil unidades habitacionais, por meio

de sua luta no MTST.”

Perto de completar 86 anos de idade,

Erundina chegou a anunciar que não

disputaria mais cargos eletivos, mas

mudou de ideia com o convite para in-

tegrar a chapa de Boulos. Tornou-se uma

peça central na campanha. A bordo de

seu “Cata-Voto”, uma espécie de papa-

móvel, no qual a deputada se protege do

coronavírus por uma cúpula de acrílico,

ela percorreu numerosos bairros da pe-

riferia para conversar com os eleitores

e pedir votos. “Os sonhos não envelhe-

cem, ainda tenho muito a contribuir”,

diz a candidata, que também enfrentou

muito preconceito ao eleger-se prefeita

de São Paulo, em 1988. “Como eles não

têm muita coisa a dizer sobre o Boulos,

apelam para essas falácias. Dizem que

ele é radical, vai tomar a casa dos outros.

Na minha época, foi pior. Imagina, uma

mulher, nordestina e pobre, no comando

da cidade mais rica do País... Só faltou eu

ser negra para completar o combo da ex-

clusão. A reação foi feroz. Chegaram a

mandar cartas com fezes para a prefei-

tura, e não foi só uma vez, não.”

Em seu sexto mandato na Câmara dos

Deputados, Erundina não poupa elogios

ao jovem colega de chapa. “Boulos é uma

liderança que veio para ficar, e não ape-

nas em São Paulo. É uma liderança pa-

ra o País”, afiança. “Na escassez de qua-

dros políticos com uma visão mais global,

mais sistêmica, mais política no sentido

pleno do termo, ele é um desses. Não sei

se tem mais outro, não. E o melhor: Bou-

los não tem aquela arrogância dos líde-

res. É um modesto, simples, que convive

fraternalmente com todos. É um homem

do povo, empoderado pela sua formação

e pelo seu compromisso com o povo.”

Na avaliação da cientista políti-

ca Vera Chaia, professora da

PUC de São Paulo, Boulos de-

monstrou muita habilidade

para aglutinar, em torno de

si, as principais legendas do

campo progressista. “Mesmo que isso

não se traduza em uma vitória nas elei-

ções deste ano, fica o legado dessa arti-

culação para o futuro, quem sabe para

a formação da tão sonhada frente de es-

querda em 2022”, avalia. “O estilo de li-

derança de Boulos favorece muito essa

união. Ele é muito tranquilo, tem um jei-

to de se expor que não expressa radicali-

dade. Além disso, é bastante carismáti-

co, no sentido de conquistar a confian-

ça dos outros para o que se dispõe a fa-

zer. Digo isso pensando no conceito de

carisma formulado pelo sociólogo ale-

mão Max Weber. Boulos consegue des-

pertar a esperança de um amplo setor

da sociedade, e isso não é pouca coisa.” •

CARTA CAPITAL

/https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.nybooks.com%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F11%2Fmarcus_1-120320.jpg)