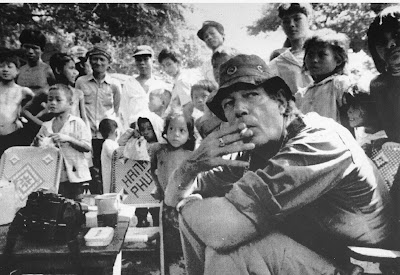

By Seth MydansTim Page, one of the pre-eminent photographers of the Vietnam War, known as much for his larger-than-life personality as for his intense and powerful combat photographs, died on Wednesday at his home in New South Wales, Australia. He was 78. His death, from liver cancer, was confirmed by his longtime partner, Marianne Harris. A freelancer and a free spirit whose Vietnam pictures appeared in publications around the world in the 1960s, Mr. Page was seriously wounded four times, most severely when a piece of shrapnel took a chunk out of his brain and sent him into months of recovery and rehabilitation. Mr. Page was one of the most vivid personalities among a corps of Vietnam photographers whose images helped shape the course of the war. He was a model for the crazed, stoned photographer played by Dennis Hopper in Francis Ford Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now.”

Michael Herr, in his book “Dispatches” (1977), called him the most extravagant of the “wigged-out crazies” in Vietnam and noted that he “liked to augment his field gear with freak paraphernalia, scarves and beads.” When a publisher asked him if he would write a book that took the glamour out of war, Mr. Herr wrote, Mr. Page exclaimed, “Take the glamour out of war! I mean, how the bloody hell can you do that?”

He went on: “It’s like trying to take the glamour out of sex, trying to take the glamour out of the Rolling Stones. I mean, you know that it can’t be done.” In a 2016 essay in The Guardian newspaper, Mr. Page described his “band of brothers” as “a hard core of photographers, writers and a few TV folks that were regulars in the field who understood the fear and the horror, yet who could still groove on its edge.” In “The Vietnam War: An Eyewitness History” (1992), Sanford Wexler wrote, “Page was known as a photographer who would go anywhere, fly in anything, snap the shutter under any conditions, and when hit go at it again in bandages.” In his later years, Mr. Page was as thoughtful as he had been flamboyant, and as articulate about the personal costs of war as he had been about its thrills. “I don’t think anybody who goes through anything like war ever comes out intact,” he said in an interview with The New York Times in 2010.

He published a dozen books, including two memoirs and, most notably, “Requiem,” a collection of pictures by photographers on all sides who had been killed in the various Indochina wars. Published in 1997 and co-written by his fellow photographer Horst Faas, “Requiem” was a memorial that he considered one of his most important contributions. The collection was put on permanent display in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. A man who had come close to death himself, Mr. Page seemed to have felt a kinship with those who had died. “At the end of the day, the mysticism of it — living, not living — becomes a mystery,” he said in 2010, “and I don’t think we are ever privileged except on death’s doorstep to actually understand it.”

His closest encounter with death came in April 1969, when he stepped out of a helicopter to help offload wounded soldiers and was hit with shrapnel when a soldier near him stepped on a mine. He was pronounced dead at a military hospital, then was revived, then died and was revived again. He finally recovered enough to be transferred to the United States, where he endured months of rehabilitation and therapy before picking up his cameras and heading back to work.

During this time, in an event that consumed much of his later life, two fellow photographers headed on motorcycles down an empty road in Cambodia in search of Khmer Rouge guerrillas and never returned. Over the following decades, Mr. Page made repeated forays into the Cambodian countryside in a futile search for the remains of the two men, Sean Flynn and Dana Stone. He had formed an intimate bond with Mr. Flynn in Vietnam. “I don’t like the idea of his spirit out there tormented,” he said during one of these trips. “There’s something spooky about being M.I.A.” He conceded that his search was also an attempt to find “a certain peace” for his own soul, to put together what he called “an enormous jigsaw puzzle, bits of sky, bits of earth.”

Timothy John Page was born in Royal Tunbridge Wells, Kent, in Britain on May 25, 1944, the son of a British sailor who was killed in World War II. He was adopted and never knew his birth mother. His name at birth was John Spencer Russell. At 17, he left England in search of adventure, leaving behind a note that read: “Dear Parents, am leaving home for Europe or perhaps Navy and hence the world. Do not know how long I shall go for.” He added instructions for paying a possible fine for a motorcycle accident and concluded, “You wouldn’t understand reasons for leaving but don’t contact authorities as I shall write periodically.” He went well beyond Europe, into the Middle East, India and Nepal, ending his journey in Laos as the Indochina war was just beginning.

e found freelance work with United Press International and won a job with photographs of an attempted coup in Laos in 1965. He spent most of the next five years covering the Vietnam War, working largely on assignment for Time and Life magazines, U.P.I., Paris Match and The Associated Press. His photography was notable for its raw drama and its intimacy with danger, the product of the risks he took to immerse himself in combat. “Perhaps Page’s most striking pictures are of the G.I.s,” William Shawcross wrote in an introduction to “Tim Page’s Nam” (1983). “Poor whites and blacks plucked from the ignorant and often innocent island of America’s heart and cast without understanding or preparation into an utterly alien and terrifying world.”

Mr. Page took a break and traveled to the Middle East to cover the 1967 Arab-Israeli war. In December of that year, he was arrested for disturbing the peace, along with Jim Morrison of the Doors, during a melee at a concert in New Haven, Conn. “I danced about with my camera shooting the punch-out,” he wrote in an essay. “An officer grabbed me and began beating me.” He was held in jail overnight.

In the 1970s, he worked as what he called a “gonzo photographer,” tripping with and covering the drug-fueled world of rock, hippies and Vietnam veterans, mostly for music magazines like Crawdaddy and Rolling Stone.

He returned regularly to Vietnam after the war to shoot assignments, run photo workshops and photograph victims of Agent Orange, the carcinogenic defoliant sprayed by the American military to clear jungles there. In 2009, he spent five months in Afghanistan as a “photographic peace ambassador” for the United Nations. He also covered turmoil in East Timor and the Solomon Islands and finally settled near Brisbane, Australia, serving as an adjunct professor at Griffith University. In addition to Ms. Harris, he is survived by his son, Kit, from his earlier relationship with Clare Clifford. At the time of his cancer diagnosis in May, Mr. Page was working on two more books as well as an archive of his photographs.

After all his escapes from death, he said, he understood that there was no recovery from his inoperable cancer. “Yeah, you know, we’ve always bounced through to the other side, and I don’t think it’s going to happen this time,” he said by telephone from Australia, soon after his diagnosis. “But hopefully it’s going to be painless.”

NEW YORK TIMES

No comments:

Post a Comment