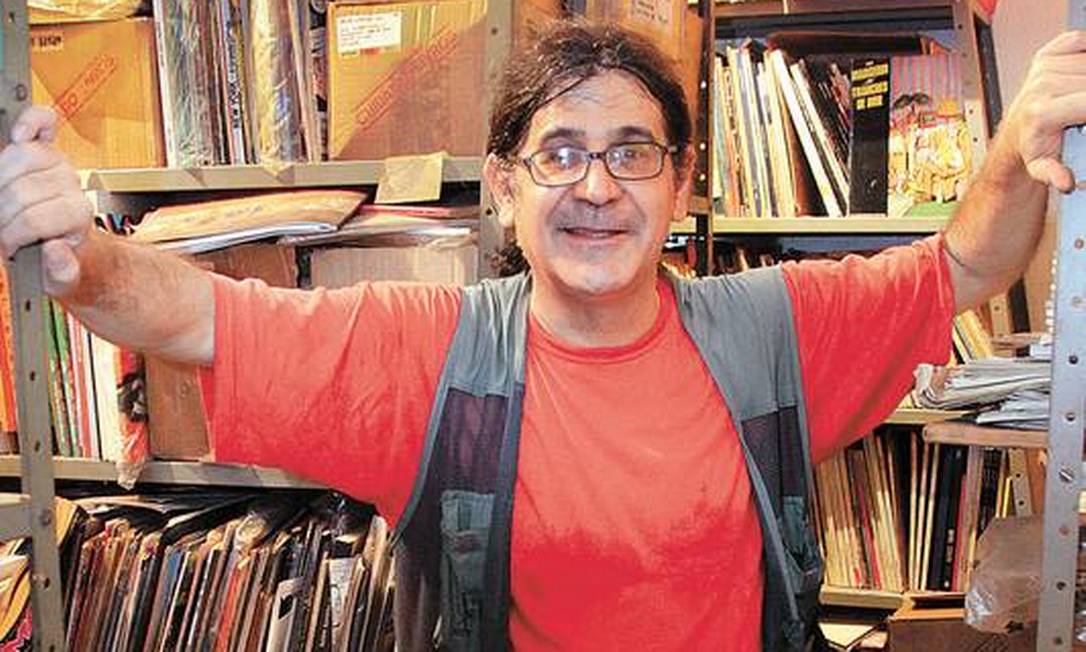

Morreu nesta sexta-feira (24) o cartunista, quadrinista e editor Ota, atuante desde os anos 1970 e que se destacou na edição brasileira da revista de humor "Mad". Otacílio Costa d’Assunção Barros, nascido no Rio de Janeiro em 1954, tinha 67 anos.

O corpo do ilustrador foi encontrado em seu apartamento na Rua Ernani Cotrim, na Tijuca, Zona Norte do Rio. A morte, causada por um mal súbito, foi confirmada ao GLOBO pela família. Ota se sentiu mal na quarta-feira (22) e queixou-se com o dono do restaurante em que almoçava todos os dias, mas voltou para casa normalmente. Como morava sozinho e não retornou ao estabelecimento nos dias seguintes, o proprietário do local, juntamente com os vizinhos, acharam estranho e acionaram a família. Ao arrombarem a porta do apartamento, encontraram o artista morto.

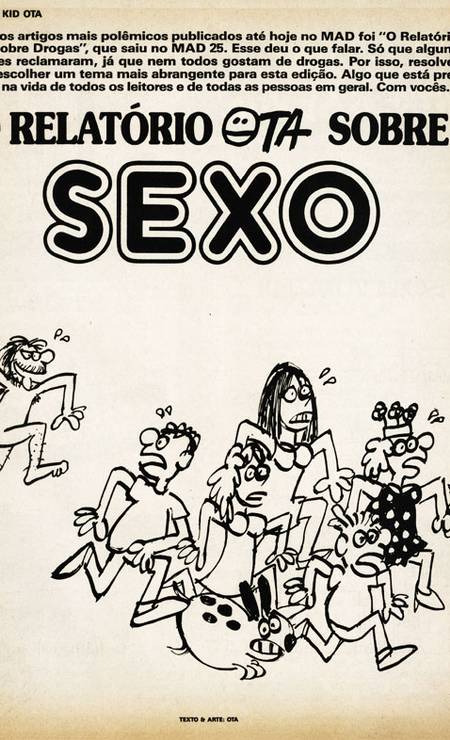

Em 1974, Ota se tornou o editor responsável pela versão nacional da "Mad", que marcaria sua carreira. Na revista, ele publicava os populares "Relatórios Ota", onde assinava arte e texto, combinado traço simples e piadas mordazes para dar sua visão sarcástica a temas como política, Rio de Janeiro, esquemas de pirâmide ou sexo.

Permaneceria na "Mad" enquanto a revista mudava de editora, saindo da Vecchi para Record (1984-2000), Mythos (2000-2006) e Panini (2008). Ao deixar a última, após um conflito profissional, declarou que iria leiloar todo o acervo relacionado à "Mad". Segundo amigos e parentes, seus últimos anos de vida foram de dificuldades financeiras.

Filho mais velho entre cinco irmãos, Ota tinha uma relação próxima com a irmã Constança e seus filhos, André d'Assunção e Iaci d'Assunção André conta que a vida do tio foi muito intensa e que ele o considera uma enciclopédia sobre produção editorial.

— Os personagens do Ota eram a vida dele. Estar perto dele era ver as referências da vida real misturadas com a fantasia. A vida pessoal dele era totalmente refletida na arte. — recorda o sobrinho. — Uma das coisas que acho mais marcante nele foi a quantidade de pessoas que ele deu oportunidade para se lançarem.

Essa característica, de dar a chance para novos talentos, é reforçada pelo jornalista e especialista em desenho de humor, Ricky Goodwin, seu amigo pessoal e colega de trabalho.

— Além de muita gente nova ter começado profissionalmente nas revistas que Ota editou, ele abria espaço para veteranos que não tinham onde publicar seus quadrinhos — recorda o jornalista.

Goodwin e Ota tornaram-se amigos na faculdade e realizaram muitos projetos juntos. Ele conta que, às vezes, era difícil acompanhar a velocidade criativa e emocional do artista. Na época do Orkut, existia uma comunidade que reunia as pessoas com quem ele tinha brigado.

— Ota podia ser irrascível mas quase sempre era incrível. O Incrível Ota. É um absurdo imenso que ele, por tudo que fez e pela sua genialidade, não ter tido, principalmente nos últimos anos, maior reconhecimento. Seus tempos finais foram sem trabalhos e sem dinheiro. Embora continuasse produzindo, sem parar — desabafa Goodwin — Os quadrinhos ainda são marginalizados no Brasil, e o Ota, um ser dos quadrinhos, vivia uma vida à margem, uma lembrança para todos que cresceram com a "Mad", mas sem espaço para a sua produção atual e sua experiência como editor.

Influência para outros artistas

Para o quadrinista e roteirista Arnaldo Branco, é grande a importância de Ota no cenário brasileiro:

— A importância dele é tremenda. Foi o primeiro contato de várias gerações com o humor gráfico, graças a seu trabalho na "Mad", que era como um "Pasquim" pra adolescentes. Fora seu trabalho como tradutor e editor de vários quadrinhos nacionais e estrangeiros — diz Branco. — Ele influenciou muito o meu trabalho. Todo desenhista de traço, vamos dizer assim, econômico deve demais ao Ota. Ele me encorajava a ser direto, cru e infame.

Branco acrescenta que conheceu Ota assim que começou a publicar:

— Era uma figura, maluco e querido. Era amado por todo mundo na cena, nunca ouvi ninguém falar uma palavra negativa sobre ele.

Marcelo Martinez, roteirista, cartunista e designer gráfico, conta que "Ota era o cartunista mais rápido do oeste".

— Era capaz de, no meio de uma conversa, sacar uma caneta, desenhar uma piada em um guardanapo e guardar de volta no bolso no colete, dizendo: "depois eu passo a limpo". Mas o desenho já estava pronto! — recorda Martinez. — Ota organizou um monte de eventos. Lançou muita gente no mercado, sempre repetindo que "para ficar bom, tem que publicar. Porque o cara vê o trabalho impresso e entende o que podia ficar melhor".

Martinez acrescenta que "para todos nós, Ota era imortal".

— Conheci o Ota numa palestra, quando estava no primeiro período da faculdade, em 1990. No final, pedi para mostrar meus desenhos. Ele disse "prepara um material e leva na editora." Fiz isso e cheguei lá uma semana depois, com a pasta caprichada. Ele: "Pô, tô saindo pra almoçar, mas deixa eu ver: isso não, isso não, isso sim. Deixa aqui e passa depois para pegar o cheque." — lembra o cartunista. — Estou sem ação. Perco meu primeiro editor, o cara que apostou nas minhas piadas, que me ligava pra pedir uma dica de fonte tipográfica e emendava o papo com ideias de revistas malucas que nunca faria.

O animador, cartunista, ilustrador e quadrinista Allan Sieber lembra com alegria o quanto Ota era "uma figura", grande colecionador de quadrinhos, com muita energia e com algumas excentricidades.

— Teve uma época que ele tinha tinha dois apartamentos, um só para quadrinhos e o outro, que ele morava, também já estava entulhado. Eu admirava o ritmo dele, ele era uma usina mesmo. E uma pessoa maluca de verdade Por exemplo: ele entrava no banho vestido, se lavava e ao mesmo tempo lavava as roupas. Saía do chuveiro com a roupa toda molhada e deixava secando no corpo. Assim, a roupa já ia ficando passada — recorda Sieber, rindo.

Fabiane Langona, cartunista e quadrinista, considerava Ota um padrinho e diz que, praticamente, se alfabetizou com o trabalho dele.

— Foi ele que me abriu as portas para a percepção de um mundo onde a gente poderia escrever bastante e desenhar menos, sem aquele academicismo — conta Langona. — Podemos ser grandes e maravilhosos, como ele era, desenhando de forma pura e autêntica.

Segundo o especialista em quadrinhos e humor gráfico Sidney Gusman, Ota está presente em muitos capítulos da história dos quadrinhos nacionais. Na opinião de Gusman, sua passagem pela Vecchi é o grande momento da carreira, como roteirista e, especialmente, como editor.

Trajetória

Formado em jornalismo na UFRJ, ota ingressou na icônica Editora Brasil-América Latina (EBAL) em 1970, permanecendo até o final de 1973, quando entrou para a Editora Vecchi. No mesmo ano, lançou pela editora Górrion três edições totalmente autorais da revista "Os Birutas", cujos personagens também foram publicados como tiras diárias no período entre 1972 e 73. Nessa mesma época colaborou para publicações underground como "A Roleta", "Vírus" e "A mosca".

Em 1974 se tornou o editor responsável pela versão brasileira da revista americana "Mad", na qual exerceria diversos cargos, deixando o título em definitivo em 2008.

Durante sua primeira fase na "Mad", Ota também foi editor da cultuada revista de terror "Spektro" a partir de 1977, até o fechamento da Vecchi, em 1983. Em 1984, publicou pela Record o livro "O quadrinho erótico de Carlos Zéfiro", uma análise que ajudou a firmar o reconhecimento em torno dos "catecismos".

Um apaixonado pela história dos quadrinhos, ele foi responsável pelas reedições de "Luluzinha" e "Recruta Zero" pela Pixel, além de ser responsável pela coleção de álbuns do personagem Asterix pela Record.

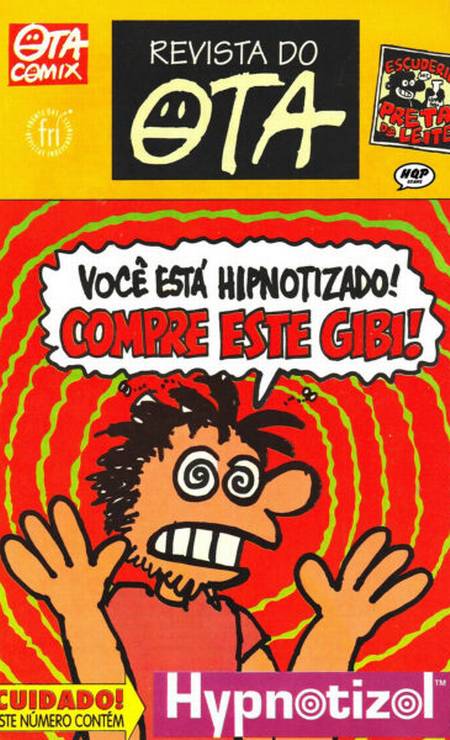

Em 1994, recebeu o prêmio de Melhor Revista Independente no Troféu HQ Mix pelo título "Revista do Ota", que teve apenas um número. Em 2005, assinou no Jornal do Brasil uma coluna sobre quadrinhos e, no ano seguinte, começa a publicar a tira Concursino para o jornal "Folha Dirigida".

Publicou de forma independente o e-book "A garota bipolar - o começo de tudo" em 2016. Em 2020, foi bem-sucedido o financiamento coletivo para publicação em papel da série, que aguarda lançamento.

Seu último trabalho público começou há quatro meses: em junho de 2021, passou a publicar tiras sobre a vida universitária no site da Faculdade Campos Elíseos, de São Paulo.

:extract_focal()/https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.newyorker.com%2Fphotos%2F6119484157b611aec9c99b43%2Fmaster%2Fw_2560%252Cc_limit%2FChotiner-Afghanistan01.jpg)