Elias Amador, músico e regente que tirou dos acordes sua principal lição de vida:

Ele aprendeu a roubar, a cheira cola e a viver nas ruas com apenas 6 anos, quando deixou a casa dos pais, em São Gonçalo, para viver perambulando entre Niterói e o Rio. Chegou a dormir, com outros meninos, diante da Igreja da Candelária. Vinte e cinco anos depois da chacina nas imediações do templo, Elias Alves Amador, de 33 anos, está casado, é pai de dois filhos, e coordena o projeto de música Amar, que atende, no Centro do Rio, a cerca de 40 jovens, entre 7 e 17 anos. Todas são moradoras de comunidades, como os morros de São Carlos, Providência, Mineira, Pinto e Prazeres.

e música pela Unirio.

O projeto funciona na Igreja Evangélica Fluminense. Para manter as aulas, Elias conta com doações. Não recebe nenhum centavo público.

— Quando vivia nas ruas, fiéis da igreja evangélica vieram, um dia, me oferecer sopa. Aos 13 anos, sem saber ler e escrever, fui acolhido pela instituição Obras Sociais de Fé e Alegria. Minha vida mudou. Aprendi a ler, a escrever e a plantar. Com 19 anos, deixei o projeto. Prestei vestibular nove vezes até ser aprovado. Agora ensino para as crianças o que aprendi.

Adilson Dias, professor e diretor teatral que foi salvo pela arte:

Professor e diretor teatral, Adilson Dias, de 38 anos, foi parar na Igreja da Candelária por uma curiosidade de menino. Aos 9 anos, resolveu ver o que tinha no fim da linha do trem da Central do Brasil. Chegou à gare da Estação Dom Pedro II, nome antigo da Central. Lá, virou engraxate de sapatos e foi ficando.

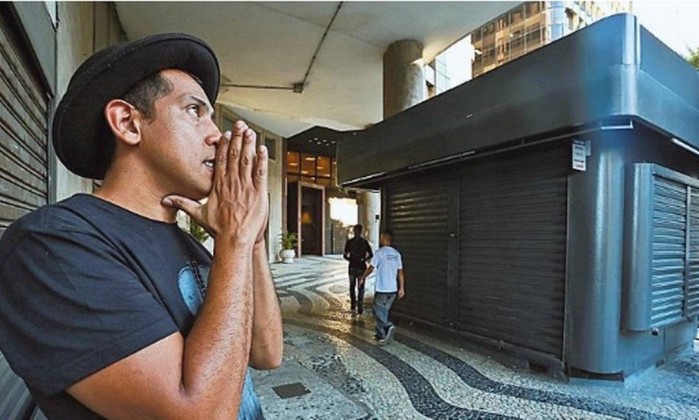

O rapaz conta que a arte o salvou. Depois de sofrer uma agressão no Centro, foi viver em frente à Casa de Cultura Laura Alvim, em Ipanema. Ele fala emocionado da virada que deu na sua vida.

— O ator Sérgio Britto, meu padrinho, me levou para fazer teatro na CAL (Casa das

Artes de Laranjeiras).

Em 2011, já diretor teatral, ganhou elogios da crítica ao dirigir “A Paixão de Cristo", na Cidade de Deus, na qual Jesus tinha cabelos black power e foi queimado dentro de pneus, como na tortura feita por traficantes, conhecida como “micro-ondas”.

— A arte me salva e me protege. Quando olho para o passado, eu vejo que é possível sonhar — diz Adilson.

Claudete Costa, coordenadora do Movimento Nacional dos Catadores, que dedicou a vida à reciclagem:

Claudete Costa, hoje com 38 anos e mãe de dois filhos, saiu de São Paulo para morar em Vassouras, no Estado do Rio, com o pai, a mãe e os irmãos. Ela estava com 8 anos.

— A gente tinha uma ótima vida, até meu pai agredir minha mãe. Deixamos tudo para trás e viemos morar na cidade do Rio. Na rua. Ficamos sob uma marquise na Rua Uruguaiana. Minha mãe catava papelão, e a gente ajudava. Ficamos ali, sem casa, por mais de quatro anos. Foi nessa época que eu conheci os meninos que viviam na Candelária — conta Claudete.

— A gente foi morar lá, mas ficava a semana toda dormindo nas ruas do Centro. Eu vivia fugindo para encontrar os meninos na Candelária. Conheci o Bochecha e vários outros garotos. Quando a chacina aconteceu, eu estava de castigo, trabalhando com minha mãe próximo à Praça Quinze — lembra.

A experiência com a mãe acabou virando profissão. Claudete, que era conhecida entre os meninos de rua como Beiçola, há 28 anos vive da reciclagem de material que recolhe das ruas. Foi eleita coordenadora estadual do Movimento Nacional dos Catadores, com representação em todos os municípios do Rio:

— O lixo me salvou. É o que eu costumo dizer. E ainda hoje me ajuda a sobreviver e a cuidar da minha família.