ZADIE SMITH

Tár

a film written and directed by Todd Field

During the first ten minutes of Tár, it is possible to feel that the critic Adam Gopnik is a better actor than Cate Blanchett. They sit together on a New Yorker Festival stage. Gopnik, playing himself, is a relaxed and fluid interviewer. His interviewee, the (fictional) conductor Lydia Tár, is stiff and self-conscious—actorly, even. As Gopnik recounts Tár’s many achievements, her face remains fixed in its pose of false humility, and when she speaks, she offers her audience a series of eloquent but overly rehearsed bons mots:

We don’t call women astronauts

“astronettes.”

Time is the essential piece of

interpretation.

You cannot start without me. See,

I start the clock.

But Blanchett has it exactly right. She

is doing what the talent is always doing

at these things: acting. Self-fashioning,

repeating witticisms they’ve used

many times before, pretending to con-

sider questions long settled in their

own minds. After which the talent goes

home, to their backstage life.

If the talent is a Cultural Luminary,

backstage is likely to be even more

glamorous than front-of-house. Pris-

tine Poggenpohl kitchens and $30,000

sectionals and discreetly disguised

safes sunk into great expanses of un-

divided wall. A loft that stretches a city

block. Such is the life of Lydia Tár. Her

daughter, Petra, attends a bourgeois

German private school and her wife,

Sharon, is first violin in Tár’s own or-

chestra, the most prestigious in Berlin.

Tár maintains a second apartment in

the city, for those moments when she

needs privacy.

Cultural Luminaries make a lot of

money. Their imperious attitudes and

witty bons mots are in demand every-

where—until they aren’t. As Tár dis-

covers the very next morning, while

guest teaching at Juilliard. Here her

charismatic lone-genius shtick—which

so delighted the gray-haired festival-

goers—falls on stonier ground. Tár is

now speaking to a different generation.

The generation that says things like

I’m not really into Bach. Such state-

ments are calculated to bring out the

hysteric in a middle-aged Cultural Lu-

minary, and Tár immediately takes the

bait, launching into an aggressive de-

fense laced with high-handed pity (for

the young man who dares say it) and

a more generalized contempt for his

cohort.

The young man is named Max.

He has a very gentle demeanor and

a sweet, open face, and seems in no

way to be seeking confrontation. Asked

how he felt about Bach, he simply an-

swered. But now, under Tár’s verbal

assault, he attempts to expand his cri-

tique: “Honestly, as a BIPOC pangender

person, I would say Bach’s misogynis-

tic life makes it kind of impossible for

me to take his music seriously. . .” The

battle lines are drawn. Max is a young

snowflake. Tár’s an Art Monster.1 She’s

also a (self-described) “U-Haul Les-

bian,” although this aspect of her iden-

tity won’t help her much. In Tár, time

is the essential piece of interpreta-

tion, and there’s an awful lot of time

these days between people in their

twenties and people in their fifties.

Sometimes it feels like the gap has

never been wider.

To paraphrase Schopenhauer—who

gets several shout-outs in Tár—

every generation mistakes the limits

of its own field of vision for the limits

of the world. But what happens when

generational visions collide? How

should we respond?

As we learn in her classroom, Tár’s

method is direct combat. For she is

Gen X—like me—and one of the strik-

ing things about my crowd is that al-

though we like to speak rapturously

of emotion in the aesthetic sense, we

prefer to scorn emotions personally

(by way of claiming to not really have

any) and also to trample over other

peoples’. It doesn’t occur to Tár that

sweet young Max may have serious

trouble with anxiety—although we in

the audience certainly notice his knees

bouncing frantically. The power differ-

ential between these two means that

a rant Tár might launch into around

a dinner table in Berlin—to much re-

ceptive laughter—is experienced as

ritual humiliation by a young man ex-

posed in front of his peers. But Tár is

discombobulated also. It’s a long climb

down from Cultural Luminary to Con-

tra, and no doubt a great shock to find

yourself so sharply reassessed and re-

defined by the generation below you.2

Do twenty-five years of glass-ceiling

breaking and artistic excellence count

for nothing? It’s enough to pitch a girl

into a midlife crisis.

What if Tár had taken a deep breath

and tried a different approach? In-

vited Max to lie under the piano, say,

while she played some Bach, then in-

quired after his feelings about that

experience? After which perhaps they

could have switched positions, with

Max playing and Tár lying down. She

might ask him what it felt like to con-

sider the music while simultaneously

considering the man who made it. Can

an A-minor chord be misogynistic? Is

an individual human ever really the

sole source of any particular piece of

music in the first place? Instead, Tár

mounts a familiar high horse:

Unfortunately, the architect of

your soul appears to be social

media. You want to dance the

masque, you must service the com-

poser. . . . You must in fact stand

in front of the public and God and

obliterate yourself.

We of Tár’s generation can be quick

to lambaste those we call (behind their

backs) “the youngs,” but speaking for

myself, I’m the one severely triggered

by statements like “Chaucer is misogy-

nistic” or “Virginia Woolf was a racist.”

Not because I can’t see that both state-

ments are partially true, but because

I am of that generation whose only

real shibboleth was: “Is it interesting?”

Into which broad category both evils

and flaws could easily be fit, not be-

cause you agreed with them personally

but because they had the potential to

be analyzed, just like anything else.3

Whereas if you grew up online, the

negative attributes of individual hu-

mans are immediately disqualifying.

The very phrase ad hominem has been

rendered obsolete, almost incompre-

hensible. An argument that is directed

against a person, rather than the po-

sition they are maintaining? Online a

person is the position they’re main-

taining and vice versa. Opinions are

identities and identities are opinions.

Unfollow!

These opposing sensibilities make

perfect sense to those born into them.

Both appear moronic and dangerous

to the other side. And so Max and Tár

really can’t with each other. It’s almost

comic how precisely each generation

intuits the trigger points of the one

before. To the popcorn-eating boomers

we must seem like so many parents

and children locked in a Jacob-and-

the-angel struggle, neither party will-

ing to concede an inch. Yet what if we

refused to let go until some form of

mutual blessing was conferred?

“You’re a fucking bitch,” Max tells

Tár.

“And you are a robot!” Tár tells Max.

B ack in Berlin, after a long day

bravely combating the youngs and

flying first class, Tár falls exhausted

into her wife’s arms. Tár is off duty in

baseball cap and cashmere, but glam-

our clings to her, and Sharon, dowdy

only by comparison, seems somewhat

in awe. And we are certainly curious

about this marriage, but in these lean

times we are even more curious about

the furnishings. The camera takes us

on a tour of objects, precisely indexed

à la Wes Anderson, but in the subdued

European palette of Michael Haneke.

Perfectly ordered scores bound in blue

cloth with unbroken spines. Immac-

ulate bookshelves. A gleaming grand

piano.

But should we pity our scandal-

ously successful Tár, just a little?

Some of the frostiness of her on-

stage life seems to have bled into

her backstage interpersonal relations.

Even her daughter calls her Lydia. Or

maybe it’s just that her family doesn’t

see her very much. Cultural Luminar-

ies travel a lot. In their brief spells

back home, they have many break-

fast and lunch meetings and proudly

drive their kids to school three days

in a row. In the gaps between work-

dates, they try to listen to what their

put-upon personal assistant is telling

them:

Assistant: I received another weird

email from Krista. How should

I reply.

Tár: Don’t.

Assistant: This one felt particu-

larly desperate.

Tár: Hope dies last.

Hope dies last. Germany has the best

idioms. Americans prefer There’s al-

ways hope! which, though cheering,

is demonstrably untrue. Everything

ends, even hope. But at this point we

don’t know what exactly has ended

or how badly, who Krista is, what has

passed between her and Tár, or who is

the guilty party. We are in Tár’s hybrid

vehicle, watching her drive Petra to

her fancy school. Petra is being bul-

lied by a classmate and Tár is off to do

some helicopter parenting. En route,

Tár and Petra recite “Who Killed Cock

Robin?,” that old nursery rhyme about

the attribution of guilt:

Who’ll toll the bell?

I, said the Bull,

because I can pull,

I’ll toll the bell.

In the schoolyard, the offending eight-

year-old girl is pointed out to Tár, who

bends down to eye level, introduces

herself—“I’m Petra’s father”—then

goes to town:

I know what you’re doing to her.

And if you ever do it again, do you

know what I’ll do? I’ll get you. And

if you tell any grown- up what I

just said, they won’t believe you.

Because I’m a grown-up. But you

need to believe me: I will get you.

Remember this, Johanna: God

watches all of us.

An electrifying scene. We are by now

used to apocalyptic bad guys with the

end of the world in mind, but it’s a

long time since I went to the movies

and saw an accurate representation of

an ordinary sinner. It reminded me of

that extraordinary Sharon Olds poem

“The Clasp,” in which a woman, angry

with her four-year-old daughter, holds

the child too hard by the wrist:

she swung her head, as if checking

who this was, and looked at me,

and saw me—yes, this was her

mom,

her mom was doing this. Her dark,

deeply open eyes took me

in, she knew me, in the shock of

the moment

she learned me. This was her

mother, one of the

two whom she most loved, the two

who loved her most, near the

source of love

was this.

Scene by scene we are learning

Tár, much as the poet’s daughter

“learned” her mother—and a lot of

what we learn is frightening. If poor

little Johanna mistakes Lydia Tár for

an omnipotent God, she’s not too far

off the mark. Conductors are godlike.

You can’t start without me. They are

the first cause of music. But women

as gods, as artists—as first causes of

anything—can still be a tricky prop-

osition, especially, for some reason,

in recent independent cinema. In the

multiplexes, superheroines are busy

flexing their much-celebrated biceps,

but over in the art houses, the concept

of the “independent woman” is being

subjected to a little narrative passive

aggression. In The Worst Person in the

World, a Gen X graphic novelist gets

terminal cancer to offset the destabi-

lizing effect of his ex-girlfriend/muse

becoming an artist herself. In Trian-

gle of Sadness, the modeling industry

is symbolically freighted with all the

many sins of late capitalism—perhaps

because it is one of the few trades in

which women are the first cause of

everything.4

But Tár is not at all like the conve-

nient symbolic females to be found

in those films. She is something far

more destabilizing and radical: a

human being in crisis. And not just

any crisis! The least fashionable on

earth: the midlife kind. I write this

not as excuse or explanation, only as

diagnosis. In any human life there are

several overlapping crises, political

and collective, individual and gener-

ational. It is of course possible to dis-

agree philosophically and politically

on their relative importance, but not

I think to deny their simultaneous ex-

istence. Yet when we are young, how

absurd does the midlife crisis seem?

Pathetic! What is wrong with these

people?

What’s wrong with these people

is that they are going to die, and for

the first time in their lives, they really

know that. In the curious case of Gen

X, we seem to be taking this shocking

revelation both personally and collec-

tively, maybe because the end of our

time and the end of time itself have

become somewhat muddled in our

minds. Our backs hurt, the kids don’t

like Bach anymore—and the seas are

rising! As the kids themselves say, it’s

a lot. Surely there should be someone

to blame for this terrible collision of

the apocalypse and our own cultural

and physical obsolescence—but who?

The millennials? Gen Z? Cock Robin?

In Tár, Gen X’s confusion of cause and

effect is sometimes too baldly stated.

We get that overfamiliar culture war

between Tár and Max. We get Tár won-

dering aloud whether Schopenhauer

can still be taken seriously, given

that he pushed his own wife down

the stairs.

But Tár is at its strongest when

channeling its existential dread

through other, more cinematic means.

When Tár goes jogging through the

Berlin woods and hears a young woman

screaming somewhere, she stops in her

tracks, with a guilty, panicked look on

her face—but is unable to locate the

source. Who is in pain? And who is to

blame? Surely not Lydia Tár? Schopen-

hauer apparently measured a person’s

intelligence by their “sensitivity to

noise”—or so a colleague informs Tár

during one of her many meetings—

and back at the loft she is woken in

the night by strange noises she can’t

identify. Is it the fridge? The air con-

ditioning? Tearing apart her expensive

home, she finds a metronome ticking

in the safe. Ticking like a countdown.

Tár is a very intelligent woman indeed,

but her sensitivities turn out to be lim-

ited in certain areas. Yes, for our Lydia,

time’s (almost) up. The bell is tolling

and it’s tolling for her.

But first, like any bad guy, she at-

tempts to cover her tracks. We

watch her e-mailing everyone she

knows in the music community to

warn them of an unstable young

woman called Krista Taylor, who may

be spreading untrue rumors about

her. Then checking Twitter to see if

said rumors have broken out into the

world. We begin to get the picture.

Krista is a young, aspiring conductor.

Tár was her mentor. Also (secretly)

her lover—although only briefly. For

Tár is one of these middle-aged peo-

ple attracted to youth and inexperi-

ence, the kind who like to be adored

but are perhaps less keen on sticking

around long enough to be “learned.”

We never meet Krista, but from our

glimpses of the many pleading e-mails

she sends Tár’s assistant, we gather

that an affair that proved seismic

for Krista barely registered on her

older lover’s radar. Now Krista can

neither reclaim Tár’s affections nor

advance in the music industry. But

for Tár, it’s as if it never happened

at all. She is already on to the next

distraction.

Spotting a hot young cellist, Olga,

in the bathroom of her workplace, Tár

later recognizes this same young wom-

an’s shoes, peeking out from beneath

those screens orchestra directors use

to preserve the anonymity of “blind

auditions.” Next thing we know Tár

has given Olga a seat in her orches-

tra. Then decides to add Elgar’s Cello

Concerto to the program, and to give

that prestigious solo to the new girl in-

stead of the first cello. And this move,

in turn, allows her to organize a series

of one-on-one rehearsals with Olga at

that apartment she maintains in the

city . . .There’s a word for this behav-

ior: instrumentalism. Using people as

tools. As means rather than ends in

themselves. To satisfy your own de-

sire, or your sense of your own power,

or simply because you can.5

What’s interesting about Tár’s mis-

use of her own power in the ethical

realm is how much it reveals about

her aesthetics. Her own refined mu-

sical sensibility meant everything

when she was arguing with Max, but

now that she’s embarking on a new

flirtation with Olga, she’s less partic-

ular. It doesn’t matter that Olga has

no preferred recording of the Elgar

or that she only knows the piece at

all from watching Jacqueline du Pré

play it on YouTube. With Tár, it’s art

for art’s sake until it isn’t. Until desire

gets in the way.

Why are some older people so at-

tracted by youth, by inexperience?

We are offered a potential answer

when age and hard experience come

a-knocking at Tár’s door. There, on the

threshold of her apartment, stands her

neighbor: a middle-aged, disheveled,

distressed, apparently mentally unwell

woman who is in need of Tár’s help.

This woman is caring for her own sick

older sister, an even more abject and

forsaken creature, whom Tár is then

forced to witness, half-naked, covered

in her own fluids, having just suffered

a fall. The old woman clings to Tár, who

recoils in horror, rushing back to the

curated safety of her own apartment—

and into her power shower—to wash

away the human stain. Later, when the

old woman is taken from the building

by paramedics—off to a nursing home

so that her younger relatives can sell

the apartment—it is Tár who becomes

the very picture of human abjection,

cowering in the hallway, spooked by

this specter of decrepitude. In this mo-

ment she is very far from being Lydia

Tár, that sophisticated, blasé Cultural

Luminary who says things like “Subli-

mate yourself, your ego, and yes, your

identity!” or “They can’t all conduct,

honey—it’s not a democracy.” That Tár

jogs every day to stave off middle-aged

spread, threatens children, and betrays

no fear or self-doubt whatsoever, not

even when poor abandoned Krista runs

out of hope and kills herself. Not even

when the board of the orchestra ad-

vises Tár to lawyer up.

The old are vampiric. The old hoard

resources. They use status and power

and youth itself to distract themselves

from the inevitable. The young are al-

ways right in their indictment of the

old. The boomers were right about the

Greatest Generation6; we were right

about the boomers7; the millennials

are right about us.8 Still, one wonders

how these same millennials, stuck with

a name that seems to enshrine the idea

of youth itself, will now deal with the

imminent loss of their own. Up to now,

when it came to generational combat,

they’ve been right about everything,

as every generation is in its own way,

only ever missing that one vital piece

of data about time and its passing:

how it feels.

Of course, not everyone who reaches

middle age has a crisis or spends

their middle years manipulating the

young or driving anybody to suicide.

But good films are not about “ev-

eryone.” They are about someone in

particular, and Blanchett’s charac-

terization of this Lydia Tár proves so

thorough, so multifaceted in its di-

mensions, so believable, that it defies

even the film’s most programmatic in-

tentions and has reportedly sent many

a young person to googling: Is Lydia

Tár a real person? She is not one in the

eyes of the algorithm, but she certainly

is in mine. She captures so clearly the

self-pity of a predator, the vanity of

a predator, the narcissism of a pred-

ator, and in one remarkable scene

comes to embody the act of predation

itself.

It happens after one of Olga and Tár’s

private rehearsals—in which nothing

remotely sexual has occurred—and

Tár is now dropping Olga outside her

building. But Olga has left her good-

luck mascot, a teddy bear, in Tár’s car

and Tár, realizing, immediately tries to

capitalize, hurrying after Olga down an

alley, which itself turns out to lead to

a filthy, damp, abject apartment com-

plex, about as far from Tár’s real es-

tate portfolio as could be imagined.

Olga is nowhere to be seen, and Tár

can’t find the right door. Now she is in

some kind of bleak inner courtyard. It

is suddenly dark. Water drips. I never

before thought Blanchett had a pred-

ator’s face, but stalking through this

dripping, Tarkovsky-esque wasteland

with those cheekbones, she looks just

like a jaguar—who is now confronted

by another predator: a large hound, in

shadow, barking at her, a symbol of

menace worthy of Kubrick. She runs,

falling over onto concrete, smashing

that beautiful face of hers. But the dog

doesn’t attack. Nobody attacks. Yet

she goes home and tells her wife and

daughter that she has been mugged.

Petra, stricken, looks at her moth-

er’s bruised and broken face and tells

her, “You’re the most beautiful person

I know.” Sorry, Petra: we beg to differ.

But is Lydia Tár the worst person in

the world? When Petra, at bedtime,

asks her mother to hold her feet to

help her sleep, Tár tenderly holds

those little feet by the heels, and by

now we know that Tár’s own Achil-

les’ heel is not love, exactly, or even

desire, but rather a powerful pride.

Where we can just about conceive of

a millennial making up a mugging for

the purposes of pity,9 Tár’s aim is to

further demonstrate that she is an

Art Monster, who refuses to commit

to any arc of trauma. (“You should

have seen the other guy,” she tells

her orchestra.) Every generation has

its fruitful and destructive narratives

of self-fashioning. This Gen X com-

mitment to emotional resilience has

certainly had its utility—for slackers,

we sure got a lot of work done!—but

also its hidden costs. How much in-

timate damage was deflected or re-

pressed when Miss Ciccone became

Madonna? When Mr. Nelson became

Prince? When Linda from Staten Is-

land refashioned herself into the Cul-

tural Luminary Lydia Tár?

I have this sense that every gener-

ation has about two or three great

ideas and a dozen or so terrible ones.

For example, Gen X nudged forward

the good idea that men should be en-

couraged to be fully involved in the

raising of their own children. Also: love

is definitely love. We thought that art-

ists (like Bach) were limited (like all

humans), but that artworks themselves

(like The Goldberg Variations) were

limitless—sites of infinite play and

boundless reinterpretation, belong-

ing as much to their receivers as their

creators. Believing this enabled many

a voracious Art Monster to consume

many an artwork—and to make a lot

of art, too.10 But “no one should pay

for anything on the Internet” needed a

little more workshopping, and it turns

out fame is not the answer to every-

thing—saving the planet is.

Some generational realizations are

world-changing and permanent. They

become almost universally accepted

and are enshrined in law and custom.11

Others get similarly enshrined but are

everywhere ignored.12 Rightly proud

is the generation that manages to get

its ethics enshrined in law. (Although

history demonstrates that one genera-

tion alone is rarely enough to achieve

this kind of truly radical change. Gen-

erational cooperation across time is

crucial.)

There is presently no law that states,

“No middle-aged person should use

any young adult as an instrument or

tool, sexually or otherwise.” But as an

ethical imperative this is one of the

very good ideas of the present genera-

tion, and it would be a good thing, ethi-

cally speaking, if Tár adhered to it. (But

it would make for a much less interest-

ing film.) Instead, she persists. Suffer-

ing from injuries incurred during the

“attack,” Tár goes to the doctor and

gets a diagnosis she mishears as nos-

talgia aesthetica. (The actual diagnosis

is notalgia paresthetica.) Gen X suffers

from aesthetic nostalgia, yes, which

itself has its uses and abuses. On the

plus side, it sometimes enables us to

make beguiling movies like Tár that

allude to Tarkovsky. On the negative

side of the ledger, we have often been

so concerned with aesthetics to the

exclusion of all else that we are liable

to confuse aesthetic failures (making

bad art) or reputational damage (in the

cultural field) with death itself.

So it goes with Tár. She is more

concerned with the death of her own

reputation than with any possible

part she might have played in the

death of Krista. Her self-love is ma-

lignant—catastrophic. But because

this is a midlife crisis, she doesn’t

change course, and even as her con-

nection with Krista becomes publicly

known—and the storm of reputa-

tional death engulfs her—she makes

an ill-advised trip to New York to

give a talk, taking Olga with her.

For her own part, Olga meets a cute,

age-appropriate guy at Tár’s event

and goes out for the evening with

him. (The fact that Olga remains

completely unaware of Tár’s sexual

interest in her provides the few mo-

ments of comic relief in this film.)

Tár is left in her fancy hotel, alone.

Midlife crises are nothing if not delu-

sional. After which Tár has nowhere to

go but back in time, to her childhood

home on Staten Island. We find her

in her old bedroom, feeling sorry for

herself, watching VHS tapes of Leon-

ard Bernstein (Greatest Generation)

talking ecstatically of music: “There’s

no limit to the different kinds of feel-

ings music can make you have! And

some of those feelings are so special,

and so deep, that they can’t even be

described in words.”

On the stairs, on her way out, Tár

bumps into her brother. He doesn’t

look like a Cultural Luminary; he’s

dressed like a man who works with his

hands. He regards his famous sister

with pity and offers a fresh diagnosis:

“You don’t seem to know where the hell

you came from or where you’re going!”

But he’s wrong about that: Tár’s going

home, to face the music. Pictures of

her and a young cellist entering a New

York hotel are all over Twitter; in the

eyes of the public a “pattern of behav-

ior” has been established. In Berlin,

her wife, Sharon, is waiting to hear

the truth, about Krista, about Olga,

about everything: “Because I deserve

that. Those are the rules.”

Every generation makes new rules.

Every generation comes up against

the persistent ethical failures of the

human animal. But though there may

be no permanent transformations in

our emotional lives, there can be gen-

uine reframings and new language and

laws created to name and/or penalize

the ways we tend to hurt each other,

and this is a service each generation

can perform for the one before. When

Sharon accuses Tár of using her, Tár

replies, “How cruel to define our rela-

tionship as transactional!” Now, that

is definitely an example of gaslight-

ing, and how would I know this with-

out millennials explaining it to me?

Similarly, when Sharon shoots back,

“There’s only one relationship you’ve

ever had that wasn’t, and she’s sleeping

in the room next door!”—well, that’s

classic Gen X guilt-tripping, and you’re

welcome.

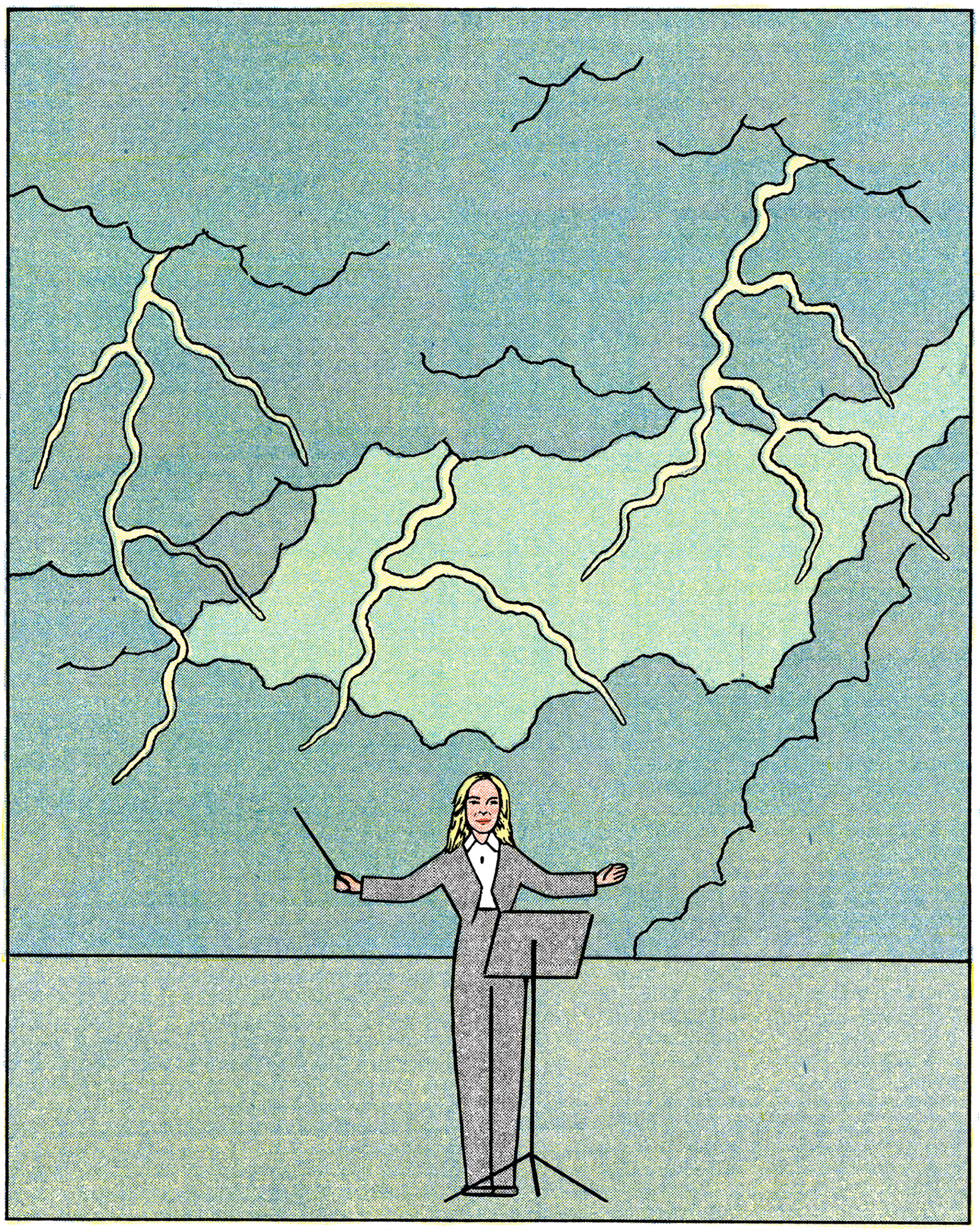

The moment I saw the poster for

Tár (Blanchett shot from below,

conducting, arms outstretched, look-

ing like Christ on the Cross) I knew I

would want to write about it, but the

film was not quite out yet, so I was

sent by Focus Features to a screen-

ing of one, in what turned out to be

the London headquarters of Google,

that great quantifier of everything.

As a committed Gen Xer, overly fond

of formulating my own aesthetic re-

sponses, I went into this movie with-

out consulting that company’s search

engines, without reading a word about

it—no interviews, no hot takes or

counter takes—and so after the cred-

its rolled, I felt very discombobulated,

full of emotions I had no words for

(yet). Later I messaged some Ameri-

can friends who began to inform me of

the general consensus forming around

this film online and the various cases

for and against it that were being

made, but before they could get very

far with all that, I asked them please

to stop. “Stand before a picture as be-

fore a prince,” suggests Schopenhauer.

“Waiting to see whether it will speak

and what it will say.” A not very dem-

ocratic piece of advice, perhaps, but,

for me, one that remains essential.

Why do female ambition and desire

have to be monstrous? Why choose a

woman to play this kind of monster

when her misdeeds are so common

among men? Or, conversely: Isn’t it

great that women now get to be just

as monstrous as anyone else? I don’t

think these questions are without

merit but I notice the way such prefab-

ricated talking points function inde-

pendently of any particular character

or film. They don’t seem to quite cap-

ture the comical specificity of Lydia

Tár’s stealing that pencil, or looming

omnipotently over an eight-year-old,

or having a manic episode, marching

around her apartment playing the ac-

cordion, singing, “You’re all going to

hell.” (Reputational damage may not

be death itself, but it can certainly feel

like ego death and even break your

brain.) And they don’t come close to

explaining or quantifying the beauti-

ful scene very near the end in which

Tár, having traveled to an unspecified

country in Southeast Asia in search

of redemption,13 stands in a waterfall

and, through a sheet of water, silently

watches a couple of happy young peo-

ple kissing.

For the first time since we “learned”

Tár, we see her stripped bare at last,

with no theory, no defense. No pre-

fabricated arguments. No witty bons

mots. She just has to “sit with it,” as

the youngs say. She is old and they

are not. Her time has passed. There is

no redemption. Nothing to be said or

done except feel it. And in this posi-

tivist world—in which our friends at

Google have indexed everything that is

the case—how I treasure any artwork

that preserves a silence or recognizes

a limit! That gestures to those aspects

of the human animal that “can’t even

be described in words.”

Tár may feel politically inadequate

to those who judge art solely in that

fashion, but I found it to be existen-

tially rich. And those among us who

prefer our baddies to be properly

punished need have no fear of dis-

appointment. In a final scene of pure

schadenfreude, we see Tár directing

what appears to be a great orchestra

once again. But then the camera turns

to the audience: she is conducting film

music, at some kind of Comic Con–

type festival, to a packed theater of

people in cosplay costumes and super-

hero suits. Tár has been relegated to

the realm of kitsch, the lowest rung

on the cultural ladder, which must

mean she has been forced to subject

her own good taste, her own fine aes-

thetic sensibility, to the demands of a

financial necessity, i.e., she has “sold

out.” And that, for a woman of Tár’s

generation—believe me—is truly a

fate worse than death. .

1“My plan was to never get married. . . .

Women almost never become art monsters

because art monsters only concern them-

selves with art, never mundane things.”

From Jenny Offill’s 2014 novel, Dept. of

Speculation, the term “art monster” has

since taken on a life of its own, appear-

ing in many essays and Twitter handles. In

April 2022 Offill appeared with the writers

Jia Tolentino and Sheila Heti in a panel at

Bennington titled “How to Be an Art Mon-

ster.” It proposed to answer the question:

“Has the age of the lone genius, willing to

sacrifice anything and everyone in their

lives for their art, come to an end?”

2This precipitous decline in social capital

has of course happened before. Boomers

went from idealistic flower children cred-

ited with transforming the social and po-

litical fabric of America to out-of-touch

fools you were welcome to roll your eyes

at: OK, boomer.

3 A mode of thinking that had its roots in

our grandparents’ generation of modernists

and New Critics. Our own (minor) innova-

tion was to transfer our critical attention

from matters like the poetry of T. S. EliOT

in movies and pop records

4And consistently paid more than men.

5At one point—in a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it

moment—Tár, while trying to bully a col-

league out of his job, steals a pencil from

his desk and hides it behind her back, for

no reason at all.

6Traumatized, emotionally stunted.

7Vainglorious hypocrites.

8Irrelevant, politically obtus

9The most famous case of this kind might

be the 2019 alleged “staged attack” on the

actor Jussie Smollett.

10We inherited and adapted this idea from

the writings of a motley collection of post-

structuralist French boomers.

11Article 4 of the Universal Declaration of

Human Rights: “No one shall be held in

slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave

trade shall be prohibited in all their forms.”

12Article 5: “No one shall be subjected to

torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading

treatment or punishment.”

13Classic Gen X move

NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

No comments:

Post a Comment