By Caitlin Dickerson

A

chaotic scene of sickness and filth is unfolding in an overcrowded

border station in Clint, Tex., where hundreds of young people who have

recently crossed the border are being held, according to lawyers who

visited the facility this week. Some of the children have been there for

nearly a month.

Children as young as 7

and 8, many of them wearing clothes caked with snot and tears, are

caring for infants they’ve just met, the lawyers said. Toddlers without

diapers are relieving themselves in their pants. Teenage mothers are

wearing clothes stained with breast milk.

Most

of the young detainees have not been able to shower or wash their

clothes since they arrived at the facility, those who visited said. They

have no access to toothbrushes, toothpaste or soap.

[Hundreds of migrant children have now been transferred out of the facility.]

“There

is a stench,” said Elora Mukherjee, director of the Immigrants’ Rights

Clinic at Columbia Law School, one of the lawyers who visited the

facility. “The overwhelming majority of children have not bathed since

they crossed the border.”

Conditions

at Customs and Border Protection facilities along the border have been

an issue of increasing concern as officials warn that the recent large

influx of migrant families has driven many of the facilities well past

their capacities. The border station in Clint is only one of those with problems.

In

May, the inspector general for the Department of Homeland Security

warned of “dangerous overcrowding” among adult migrants housed at the

border processing center in El Paso, with up to 900 migrants being held

at a facility designed for 125. In some cases, cells designed for 35

people were holding 155 people.

“Border

Patrol agents told us some of the detainees had been held in

standing-room-only conditions for days or weeks,” the inspector

general’s office said in its report, which noted that some detainees

were observed standing on toilets in the cells “to make room and gain

breathing space, thus limiting access to the toilets.”

Gov.

Greg Abbott of Texas on Friday announced the deployment of 1,000 new

National Guard troops to the border to help respond to the continuing

new arrivals, which the governor said have amounted to more than 45,000

people from 52 countries over the past three weeks.

“The

crisis at our southern border is unlike anything we’ve witnessed before

and has put an enormous strain on the existing resources we have in

place,” Mr. Abbott said, adding, “Congress is a group of reprobates for

not addressing the crisis on our border.”

The

number of border crossings appears to have slowed in recent weeks,

possibly as a result of a crackdown by the Mexican government under

pressure from President Trump, but the numbers remain high compared to

recent years. The overcrowding crisis has been unfolding invisibly, with

journalists and lawyers offered little access to fenced-off border

facilities.

The reports of unsafe and

unsanitary conditions at Clint and elsewhere came days after government

lawyers in court argued that they should not have to provide soap or

toothbrushes to children under the legal settlement that gave Ms.

Mukherjee and her colleagues access to the facility in Clint. The result

of a lawsuit that was first settled in 1997, the settlement set the

standards for the detention, treatment and release of migrant minors

taken into federal immigration custody.

Ms.

Mukherjee is part of a team of lawyers who has for years under the

settlement been allowed to inspect government facilities where migrant

children are detained. She and her colleagues traveled to Clint this

week after learning that border officials had begun detaining minors who

had recently crossed the border there.

She

said the conditions in Clint were the worst she had seen in any

facility in her 12-year career. “So many children are sick, they have

the flu, and they’re not being properly treated,” she said. The

Associated Press, which first reported on conditions at the facility

earlier this week, found that it was housing three infants, all with

teen mothers, along with a 1-year-old, two 2-year-olds and a 3-year-old.

It said there were dozens more children under the age of 12.

Ms.

Mukherjee said children were being overseen by guards for Customs and

Border Protection, which declined to comment for this story. She and her

colleagues observed the guards wearing full uniforms — including

weapons — as well as face masks to protect themselves from the

unsanitary conditions.

Together, the

group of six lawyers met with 60 children in Clint this week who ranged

from 5 months to 17 years old. The infants were either children of minor

parents, who were also detained, or had been separated from adult

family members with whom they had crossed the border. The separated

children were now alone, being cared for by other young detainees.

“The

children are locked in their cells and cages nearly all day long,” Ms.

Mukherjee said. “A few of the kids said they had some opportunities to

go outside and play, but they said they can’t bring

themselves to play because they are trying to stay alive in there.”

When

the lawyers arrived, federal officials said that more than 350 children

were detained at the facility. The officials did not disclose the

facility’s capacity but said the population had exceeded it. By the time

the lawyers left on Wednesday night, border officials told them that

about 200 of the children had been transferred elsewhere but did not say

where they had been sent.

“That’s what’s keeping me up at night,” Ms. Mukherjee said.

Some

sick children were being quarantined in the facility. The lawyers were

allowed to speak to the children by phone, but their requests to meet

with them in person and observe the conditions they were being held in

were denied.

The children told the

lawyers they were given the same meals every day — instant oats for

breakfast, instant noodles for lunch, a frozen burrito for dinner, along

with a few cookies and juice packets — which many said was not enough.

“Nearly every child I spoke with said that they were hungry,” Ms.

Mukherjee said.

Another group of

lawyers conducting inspections under the same federal court settlement

said they discovered similar conditions earlier this month at six other

facilities in Texas. At the Border Patrol’s Central Processing Center in

McAllen, Tex. — often known as “Ursula” — the lawyers encountered a

17-year-old mother from Guatemala who couldn’t stand because of

complications from an emergency C-section, and who was caring for a sick

and dirty premature baby.

“When we

encountered the baby and her mom, the baby was filthy. They wouldn’t

give her any water to wash her. And I took a Kleenex and I washed around

her neck black dirt,” said Hope Frye, who was leading the group,

adding, “Not a little stuff — dirt.”

After

government lawyers argued in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in San

Francisco this week that amenities such as soap and toothbrushes should

not be mandated under the legal settlement originally agreed to between

the government and migrant families in 1997 and amended several times

since then, all three judges voiced dismay.

Among the guidelines set under the legal settlement are that facilities for children must be “safe and sanitary.”

The

Justice Department’s lawyer, Sarah Fabian, argued that the settlement

agreement did not specify the need to supply hygienic items and that,

therefore, the government did not need to do so.

“Are

you arguing seriously that you do not read the agreement as requiring

you to do anything other than what I just described: cold all night

long, lights on all night long, sleeping on concrete and you’ve got an

aluminum foil blanket?” Judge William Fletcher asked Ms. Fabian. “I find

that inconceivable that the government would say that is safe and

sanitary.”

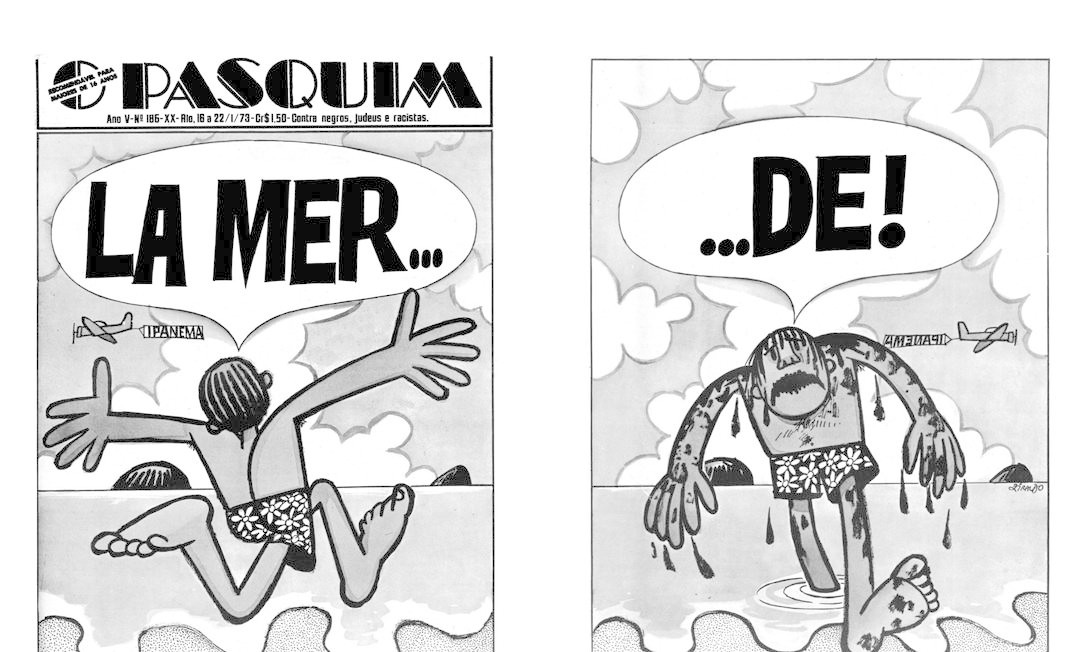

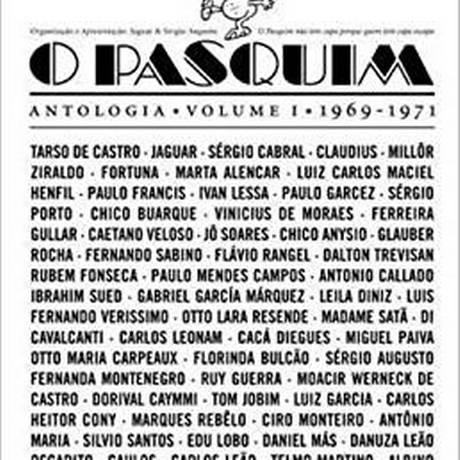

O documentário, dividido em duas partes, fala sobre os bastidores do jornal e será exibido pela SescTv nesta quarta-feira (26), às 20h e às 23h, respectivamente. Com direção de Louis Chilson, a atração também vai ao ar nos dias 28/6, sexta, a partir das 23h; e 30/6, domingo, a partir das 14h30.

O documentário, dividido em duas partes, fala sobre os bastidores do jornal e será exibido pela SescTv nesta quarta-feira (26), às 20h e às 23h, respectivamente. Com direção de Louis Chilson, a atração também vai ao ar nos dias 28/6, sexta, a partir das 23h; e 30/6, domingo, a partir das 14h30.

Foi nas páginas do Pasquim que Henfil popularizou os fradins, personagens que passaram a ser a marca registrada de sua obra. Com direção de Angela Zoé, o documentário sobre o cartunista tem depoimentos de nomes como Ziraldo, Jaguar, Sérgio Cabral e Tárik de Souza.

Foi nas páginas do Pasquim que Henfil popularizou os fradins, personagens que passaram a ser a marca registrada de sua obra. Com direção de Angela Zoé, o documentário sobre o cartunista tem depoimentos de nomes como Ziraldo, Jaguar, Sérgio Cabral e Tárik de Souza.