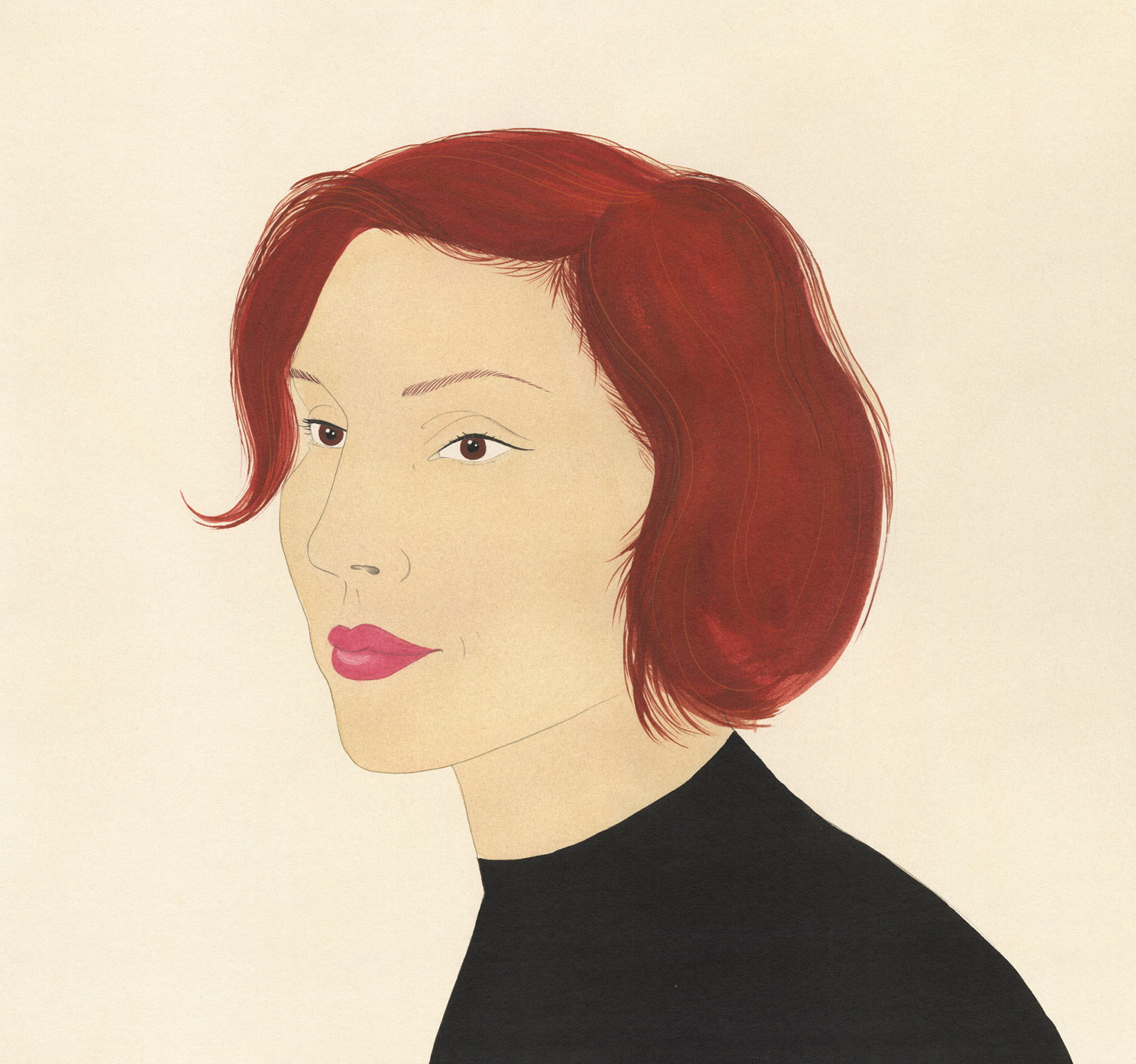

Clarice Lispector; illustration by Harriet Lee-Merrion

In Clarice Lispector’s newspaper columns and crônicas, she seems sensorially overcharged by the quotidian, needing only the tiniest slice of existence to feed her writing.

The cronista hunts big game with a pocketknife. A brief description of the old neighborhood soccer team suggests the unrelenting passage of time; a glimpse of a stranger’s arm during a turbulent flight leads to a reflection on life and death. “There’s a right way to start a crônica by using a triviality,” Machado de Assis, one of the first great writers to champion the form, wrote in 1877.

One says: how hot it is! How unwaveringly hot! One says this while shaking the tips of a handkerchief, snorting like a bull, or simply agitating one’s overcoat. Then one slips from the heat to atmospheric occurrences, drawing a few speculations about the sun and the moon, others about yellow fever, sending a sigh to Petrópolis, and la glace est rompue; the crônica has begun.

As with almost everything he wrote, there’s a subtle irony in Machado’s suggestion that an easy step-by-step will lead to the desired outcome. Shorter and more elliptical than an essay, the Brazilian crônica is in fact a maddeningly elusive genre. The difficulty lies not so much in identifying the form’s attachment to the mundane (simple prose, wry personal anecdotes, an eye for the odd detail or fleeting character), but in the specific magic dust that transforms minor observations into prose that’s brimming with pathos. The underground passage from triviality to transcendence is hard to locate, yet you know a true crônica when you read one.

The ratio of failure to success is

high, but when it works it is indelible.

It is a form that is at once high- risk—

because hard to master—and complacent,

perfect for the talent wasters,

the boozers and sinecure seekers who

can’t always endure enough solitude to

write novels. The genre’s birth, or at

least its first wave of popularity, can

be traced to the expansion of Brazilian

cities, particularly Rio de Janeiro,

and the local press in the nineteenth

century. Once a stylish reprieve from

the urgent news articles it accompanied,

the crônica has seen a severe

decline in influence over the past

decades.*

*One notable exception is Antonio Prata,

whose crônicas for the newspaper Folha

de S. Paulo not only maintain the artistic

principles that first animated the genre but

also are popular among readers.

There are writers working

today who define themselves as cronis

tas, but in the age of furious tweets

and bloated newsletters, such a subtle

form seems unlikely to regain ground.

Much like the flaneur drifting around

Paris, the cro nis ta is often thought of

as both a product and an observer of

Rio’s chaotic growth—a nocturnal, dipsomaniac

figure who sketches the fleeting

scenes and characters of the city.

Unlike the flaneur, though, the cro nis ta

is no loner; he (almost always a he)

feeds on companionship and cliques.

His paths through the city contain longer

pit stops at bars and restaurants;

he is more idler than wanderer.

An aura of thwarted promise hovers

over even the most celebrated practitioners

of the form. Not because they

failed to achieve worldly success, but

because to be a cronista is to celebrate

what is minor, to show a certain indifference

toward literary greatness. It

was Rubem Braga who came closest

to elevating the crônica to canonical

status. Having worked from the 1930s

through the 1970s, he is now probably

the writer most associated with the

form, and the main representative of

its last great generation. Braga and

his group of friends contributed to

Rio’s bohemian landscape as much

as the bossa nova musicians, writing

about one another and creating a mythology

around themselves that made

them seem elegiac from the outset,

as if they knew that their way of expressing

themselves would one day

be outgrown.

Although she often appears in anthologies

of the genre, Clarice

Lispector occupies a peculiar position

in the history of cronismo. She was a

latecomer, writing her first crônicas

in the last decade of her life, but her

presence in the daily papers gave her

the readership that had long eluded

her as a writer of fiction. The critical

and commercial success of her first

novel, Near to the Wild Heart (1943),

published when she was only twentythree,

had been followed by a string

of commercially disappointing novels,

earning her a reputation as an author

who was “hermetic” (an adjective she

hated) and hard to sell. Braga and his

friends, fierce admirers of her fiction,

used their influence to promote her

journalistic career, recommending her

fiction in 1958 to Senhor, an influential

little magazine where she would

become a regular contributor. But it

was her hiring by the Rio daily Jornal

do Brasil in 1967, a few years after she

wrote the book that is now considered

her masterpiece, The Passion According

to G.H. (1964), that brought her to

the attention of a wider public. She

held the job until 1973, four years before

her premature death from cancer.

It was the press that put Lispector on

a first- name basis with the Brazilian

public, like a soccer player, musician,

or politician. “Thanks to the Jornal do

Brasil I’m becoming popular. I get sent

roses,” she wrote in a column in 1967.

Too Much of Life: The Complete Crônicas,

translated by Margaret Jull Costa

and Robin Patterson, is mostly made

up of her pieces for the daily, though

a sprinkling of writings for other publications

is also included. The second

half of the title is misleading. Only

a few pieces in this collection would

fit even the loosest definition of a

crônica—they vary widely and include,

among other miscellany, reflections

on writing; miniprofiles of friends,

artists, and artist friends; cryptic dialogues;

replies to fan mail; a spiky

riposte to a rumor about the author’s

divorce; and one indignant letter, in

the Moses Herzog vein, to the minister

of education. Also, unclassifiable

sentences and paragraphs. Few writers

have ever taken the expression “This is

an open space” quite so literally. Costa

and Patterson’s translation does a fine

job of capturing Lispector’s syntax and

rhythms, a task that isn’t so straightforward

considering the sheer variety

of forms her pieces take.

Tucked away in these nearly 750

pages, like rare flowers among ordinary

grasses, are more purposeful

attempts at writing what one might

call pure crônicas, some of which are

perfectly rendered, and a handful of

which have the unmistakable touch

of the author. These are the ones that

most often appear in anthologies, and

upon which Lispector’s reputation as

a cronista rests.

“When I was very young,” she writes

on June 6, 1970, in “Fear of Eternity,”

“I’d still never tried chewing gum, and

it wasn’t much talked about even in Recife.

I had no idea what it was.” This is

a typical setup for a crônica: a personal

memory or perception—Machado’s

triviality—clearing only the faintest

path to a theme hinted at in the title.

Her sister warns her not to lose the

never- ending candy (“It lasts a whole

lifetime”), alarming little Clarice:

I picked up that small pink pastille

representing the elixir of eternal

pleasure. I examined it, scarcely

able to believe in that miracle. I,

who, like other children, would

sometimes take a still intact

piece of candy out of my mouth

in order to suck it later on and so

make it last longer. And there I

was with that seemingly innocent

pink thing, making possible the

impossible world I had only just

become aware of.

Lispector here nails the form’s paradoxical

mixture of accessibility and

high artistic ambition by conjoining a

childhood memory with the unbearable

weight of eternity. “Suck it and enjoy

the sweetness,” her sister orders. “And

then you can chew for the rest of your

life. Unless you lose it, that is, and I’ve

already lost quite a few.” As the gum

becomes rubbery and gray and tasteless,

Clarice starts to feel panicked;

eventually she spits it onto the sandy

ground at the school gates, pretending

she has lost it. “I felt shamed by her

kindness, ashamed that I had lied,” she

says. “But relieved too. No longer burdened

down by the weight of eternity.”

In Lispector’s most fully achieved

crônicas, the trivial doesn’t so much

segue into the transcendent as become

inextricable from it. A piece of gum

contains the whole space– time continuum;

a mercury droplet represents the

elusive nature of all material things.

This is the same sense of rapture one

hears from her hypersensitive fictional

narrators, to whom no ordinary thing

fails to carry some extraordinary emanation—

an encounter with a cockroach

evokes the vision of a terrible, boundless,

amoral universe, the liquid oozing

out of it a damning nectar containing

the whole secret of human existence.

Often, though, Lispector just seems

to fret about her new day job. “I

know that what I write here cannot

really be called a crônica or a column or

even an article,” she writes on March 9,

1968. That same year, she asks, “Is the

crônica a story? Is it a conversation? Is

it the summation of a state of mind?”

Dwelling on one’s desire, ability,

or lack thereof to master the form—

metacronismo, say—is not unusual.

But there is something wildly incongruous

about Lispector as cronista—

it’s as if J.M. Coetzee had been invited

to write weekly op- eds for the Times,

or Cormac McCarthy hired as a regular

book critic. Where the form privileges

levity, suppleness, storytelling, and a

certain sense of humor, her writing

is often abstract, weary, and wary of

language’s limits, impatient not merely

with narrative but with events in general,

always seeking a fast track to

metaphysical experience. “As a reader,

I prefer the attractive type of book,

because it’s less tiring, less demanding,

requires little real engagement,”

she wrote on February 14, 1970. “But

as a writer, I want to dispense with

everything I can possibly dispense

with: that is what makes the experience

worthwhile.”

Her primordial world of animals,

rocks, plants, and anthropomorphic

rooms doesn’t really jibe with the secular,

street- smart world of odd characters

and sly observations, the gossipy

tone one finds in writers like Braga.

Often, in her weekly pieces, she slips

into a novelistic voice that, one suspects,

reflects the kind of thing she’d

rather be doing. A column published

on October 10, 1970, begins:

It was very dry that spring, and

the radio crackled, picking up

static, our clothes bristled with

static electricity, our hair clung

to the comb as if magnetized:

it was a hard spring. And very

empty. Wherever you happened

to be, you set off into the distance:

never had there been so

many paths. We spoke little; our

bodies heavy with sleep, our eyes

wide and blank. On the balcony,

along with the fish in the aquarium,

we drank a cool drink, gazing

out at the countryside. The dreams

of the goats wafted in from the

fields on the breeze. At the other

table on the balcony sat a solitary

faun. We stared into our drinks and

dreamed static dreams inside the

glass. “What did yu say?” “I didn’t

say anything.”

It’s heady to picture my grandfather

back in vast, isolated Mato Grosso in

the late 1960s, nursing his ulcer and

stirring his ground guarana leaves

while opening his paper and finding

this sort of writing. But readers were

probably not that fazed. Lispector’s

enigmatic style was certainly unique,

but part of the whole point of crônicas

is their unapologetic lack of utilitarian

value, their beautiful pointlessness.

They are a kind of anti- news.

The journalist Flávio Pinheiro—

who did not cross paths with Lispector

at the Jornal do Brasil but worked

there in the late 1970s and then again

in the 1980s and 1990s as the editor of

the famed CadernoB supplement that

she used to write for—recently told

me that the cronista’s role back then

was to “enhance the paper’s vocabulary.”

According to him, cronistas rarely

ever went into the office, and were a

group apart, largely exempt from the

daily routine.

In a preface to the Brazilian edition

of The Complete Crônicas, released by

the publishing house Rocco in 2019, the

writer and journalist Marina Colasanti,

then the young employee who was put

in charge of dealing with Lispector’s

pieces, recalls seeing her only a handful

of times, right after she began as

a contributor. After that, her pieces

would usually come via emissary, in big

brown envelopes, written in a difficult

scrawl—the result of a home fire that

almost killed her in 1966, leaving her

writing hand severely damaged. Very

little editing went on: “I fixed one typo

or another, not more than that,” Colasanti

writes.

In one sense Lispector was a part of

Braga’s gang. According to Benjamin

Moser, the author of Why This World:

A Biography of Clarice Lispector (2009),

it was Otto Lara Resende, another cronista,

who in 1960 first suggested to

the then editor of Jornal do Brasil, Alberto

Dines, that he hire Lispector as

a regular writer. In 1962, a few years

after divorcing her husband, the diplomat

Maury Gurgel Valente, Lispector

had a brief and intense affair with

Paulo Mendes Campos, a well- known

cronista from Braga’s group who was

married at the time. And it was Braga

and Fernando Sabino who published

The Passion According to G.H., through

their own small publishing house.

But these close relationships belie

Lispector’s separateness. The most

glaring difference, of course, was her

gender. Along with Cecília Meireles

and Rachel de Queiroz, Lispector is

among the very few women associated

with a male- dominated genre. The

ideal occupations for cronismo—boozing

and idling, mostly—demand gargantuan

amounts of time, something

that pretty much only men had in the

heyday of the form. Though the income

she received as a diplomat’s wife (first

in Naples, later in Washington) gave

her a certain amount of freedom to

write, Lispector longed for home. Her

second, third, and fourth novels were

all written abroad with difficulty, between

attending diplomatic functions

and taking care of her two boys, and

the cold reception of publishers back

in Brazil depressed her.

Reeling from her divorce, she returned

to Rio in 1959 with her sons

and hardly seemed to have the appetite

to take part in a literary scene built

on barhopping. Moser’s descriptions

of this period give Lispector the air

of a Ferrante character: the female

artist only half- belonging, unraveling

even while being the center of intellectual

admiration, calling friends

up in the middle of the night, taking

sleeping pills and chain- smoking

(hence the fire), using heavier makeup

to shock herself into a new persona,

consumed by her domestic life while

her male counterparts drink, selfmythologize,

and launch new literary

ventures. Mendes Campos, after their

affair, went back to his English wife

and children; Gurgel Valente sent her

$500 every month, but financial anxiety

became an issue.

Jornal do Brasil was not Lispector’s

first experience in journalism. In

1940, a few years before publishing her

first novel, she convinced a government

official and censor to give her

a job as a reporter and editor for the

Agência Nacional, a press agency controlled

by the Department of Press and

Propaganda of the Estado Novo, a dictatorial

regime installed by then president

Getúlio Vargas. Shortly afterward

she worked at the daily A Noite, also

under Vargas’s watch.

In 1952 Braga gave her a women’s advice

column at Comício, an anti- Vargas

weekly he was running at the time.

Lispector gave cosmetics and relationship

advice under the pseudonym

Tereza Quadros, occasionally smuggling

in material that subtly questioned

female stereotypes. After her

divorce she worked as a ghostwriter

for the model and actress Ilka Soares

and was again hired as an advice columnist

by the newspaper Correio da

Manhã, this time using an anglicized

pseudonym, Helen Palmer. Part of her

job was to lure unwitting readers toward

the benefits of Pond’s face cream,

which was never explicitly mentioned

in the pieces.

None of these early writings are

included in Too Much of Life, but

Lispector’s former selves often reappear

in her Jornal do Brasil columns.

In a piece dated April 24, 1971, she describes

the pleasure she finds translating

an Encyclopedia for Women:

Every woman should have one (it

isn’t ready yet), since it covers culture

(the section I’ve been doing up

till now, and I just hope they’ll also

give me the section on makeup) as

well as things that are strictly feminine

like makeup, lifestyle, handicrafts

(I’ve embroidered numerous

tablecloths, but only in flat stitch

or satin stitch—I don’t know how

to do complicated stitches), etc.

Then she says, “For women, our turn

has finally come: we are considered

important enough to be given an

encyclopedia.”

Lispector often shows this kind of

sardonic awareness about the terrible

deal women get. But she also seems

to be a pragmatist at heart, preferring

to navigate the world as it is rather

than confront it too forcefully. (That

the aforementioned ironic comment

ends the column rather than starting

it sums up this attitude.) Politically,

she declares herself a leftist. “I would

like to see a socialist government in

Brazil,” she writes on December 30,

1967. But other discussions about politics

in the columns are sparse and

generic. Whether this is because of

or despite the fact that in 1968 the

military government clamped down

on civil liberties, leading to the most

repressive period of the regime, is a

question that is hard to answer.

Writing a column under her own

name was not something Lispector

undertook lightly at Jornal do Brasil.

In a column dated June 5, 1971, she

writes, “One day I phoned Rubem

Braga, the creator of the crônica,” reminding

us yet again of his stature.

Worrying that her pieces were becoming

“excessively personal,” she asks for

his advice. “It’s impossible not to be

personal in a crônica,” he tells her. She

writes, “But I don’t want to tell anyone

about my life: my life is rich in experiences

and vivid emotions, but I don’t

ever want to publish an autobiography.”

There is a paradox in Lispector’s

fiction: despite her use of the first

person, her narrators often betray little

background. What comes across

is a sense of self- effacement, or of

self- scattering, self- dispersion—the

narrator is so sensitive to the mood,

atmosphere, and objects surrounding

her, pulling her in different directions

and down rabbit holes of abstract reflection,

that the traits usually associated

with a stable character or persona

(psychological details, biographical

facts) seem beside the point.

To this can be added a certain freedom

from the distraction of careerism.

Lispector was not immune to criticism,

but no other Brazilian novelist of the

twentieth century—no other Brazilian

novelist ever, perhaps—seemed

more unselfconscious about what was

going on elsewhere, or more aloof from

what other people were interested in,

utterly free from the usual inferiority

complexes that weigh on artists from a

huge, peripheral country that worries

about being irrelevant. In the archipelago

of postwar Brazilian fiction—precariously

united by a common language

and the ruins of a modernist project—

hers is the most self- sufficient island.

This aloofness infused her fiction

with a peculiar originality. More surprising

than her astonishing debut at

age twenty- three was the speed with

which she discarded gifts other writers

would kill for, moving quickly from

a modernist style to more mystical

writing. Shifting among the points of

view of three characters, Near to the

Wild Heart is an embarrassment of

riches, hinting at the inventive syntax

she later became known for while

also representing acute psychological

portrayals and a deft use of stream

of consciousness. Whereas the more

realist work of the great modernists

is usually deemed more “accessible,”

in Lispector’s case the early modernist

novel plays the role of the “easier”

book. (She was baffled by comparisons

to Joyce, Woolf, and Proust; she

claimed she hadn’t read any of them

before writing her first novel.)

In hindsight, it is not hard to understand

why critics were initially flummoxed:

the trajectory from almost fully

formed modernist to sui generis mystic

isn’t a usual one. By the time of The

Passion According to G.H.—the religious

allusion isn’t ironic—Lispector

was tuned into the unseen, her narrators

all seemingly overcome by a toolong

stare into the Aleph. For those

who don’t get her half the time (I count

myself among them), Near to the Wild

Heart remains the work to be cherished,

more tethered and in touch with

down- to- earth anxieties, like whether

to get married, have a kid, and so on.

“You pick up a thousand waves I

can’t catch,” Braga wrote to her in

1957, referring to her novels. “I feel

like a cheap radio, only getting the station

around the corner, where you get

radar, television, shortwave.” The compliment

sheds light on her unusual position

as cronista—why seek a glimpse

of transcendence when most of the

time you’re in a full- blown trance? If

Complete Crônicas is a misnomer, the

other half of the collection’s title, Too

Much of Life, is apt. The impression

Lispector gives is not that she is uninterested

in the quotidian, but rather

overwhelmed by it, sensorially overcharged

by the smallest occurrences,

needing only the tiniest slice of existence

to feed her fiction.

An ambivalence toward “chasing

after money, work, love, pleasures,

taxis and buses” can be a disadvantage

for reporting. Lispector’s profiles of

artists are laudatory, showing not the

slightest inclination to find fissures

in their public image. Her book and

art reviews read like press releases.

(Among these is a plug for Braga and

Sabino’s second publishing house.) Her

interviews are whimsical but without

the suggestive depth of her fiction. She

asks Pablo Neruda, who is “extremely

nice,” questions like “What is anxiety?”

and “Who is God?” as well as “Where

would you like to live if you didn’t live

in Chile?” and “What, in your opinion,

makes a pretty woman?” When she

asks him to write a poem on the spot,

he demurs. “What is love, Zagallo?”

she asks, apparently in all seriousness,

of the manager of Brazil’s 1970 World

Cup soccer team.

Sometimes she is saved by her subjects,

who indulge her in a way they

probably wouldn’t someone less famous.

Glória Magadan, a Cuban- born

writer of soap operas, answers her

heroine’s occasionally banal questions

with warm candor. “Given the influence

you have with the general public,

couldn’t you raise your level a little?”

Lispector asks, probably without sensing

her own snobbery. “I would lose

my influence then,” Magadan replies.

Yet these shortcomings never grate.

Perhaps we are as starstruck as her

star interviewees. Or more likely it’s

that her attempt to navigate the discomfort

of weekly exposition actually

produces a pure and mundane portrait,

and complicates her immaculate literary

image. In her column of September

18, 1971, she relays a rumor that

disturbs her:

Someone told me that Rubem

Braga said I am only good in books,

and that I don’t write a good column.

Is that true, Rubem? Rubem, I

do what I can. You do it better, but

you shouldn’t require others to do

the same. I write columns humbly,

Rubem. I don’t have any pretensions.

But I receive letters from

readers and they like my columns.

And I like to receive those letters.

I like to receive those letters: there is

something thrilling in this unguarded

tone, which is heard often in the collection.

To one reader, whose letter mixes

“aggression with flattery,” she says:

“You’re quite right to want me, like

Chekhov, to write amusing things. . . .

Don’t worry, Francisco, my moment to

say amusing things will come, I really

am full of highs and lows.” To another,

who speculates on her divorce:

I reckon you’re the wife of a diplomat.

You adopt an air of false

pity. . . . Madam, please keep your

pity to yourself, I don’t need it. And

if you want to know the truth, something

you weren’t expecting, here it

is: when I separated from my husband,

he waited for me to come back

to him for more than seven years.

When a “rather disheveled young

woman” shows up at her house uninvited,

paper in hand, and mentions

that she knows Lispector is an insomniac

because she can see her light

on every night—also saying that she

witnessed “the fire”—she is invited

in. The woman cooks an octopus for

her. Lispector’s editor is not thrilled

about this sort of engagement with

readers—he eventually asks her to

stop dealing so much with fan mail.

This raw sincerity and artlessness is

one of the most appealing aspects of

Too Much of Life. Even more so than in

her fiction, in her crônicas and other

columns Lispector uses the “I” without

the self- conscious, manipulative

care often employed by more autobiographical

writers (Philip Roth, say),

and the impression given is one of

vulnerability. “Fear of Eternity” and

others deserve their place among the

masterful examples of the crônica,

but it is remarkable how infrequently

Lispector tried to write these perfect

set pieces. Maybe the personal charm

and autobiographical self- presentation

demanded by the crônica—and even

by a regular column—was a little too

much for someone whose fiction always

showed a deep hesitation regarding

the idea of a unified, confident self.

The self remains fragmented, inconsistent,

rather comfortable with its

contradictions. .

Reviewed:

Too Much of Life: The Complete Crônicas

No comments:

Post a Comment