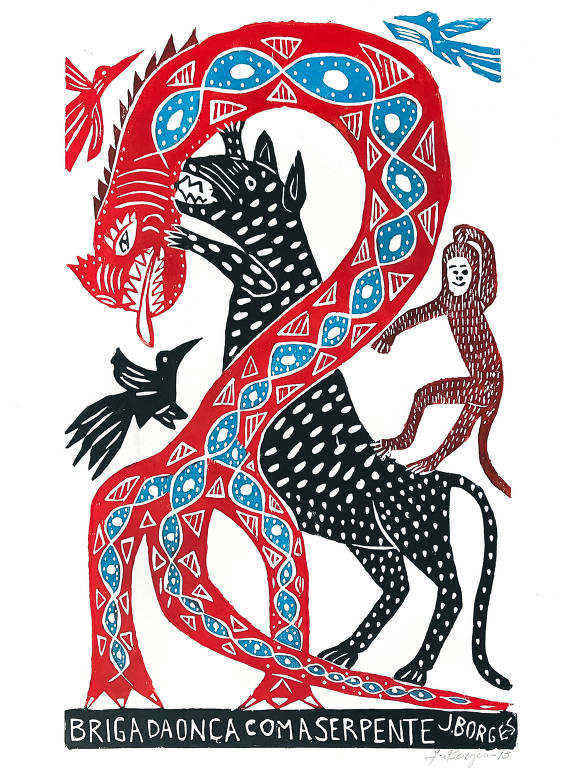

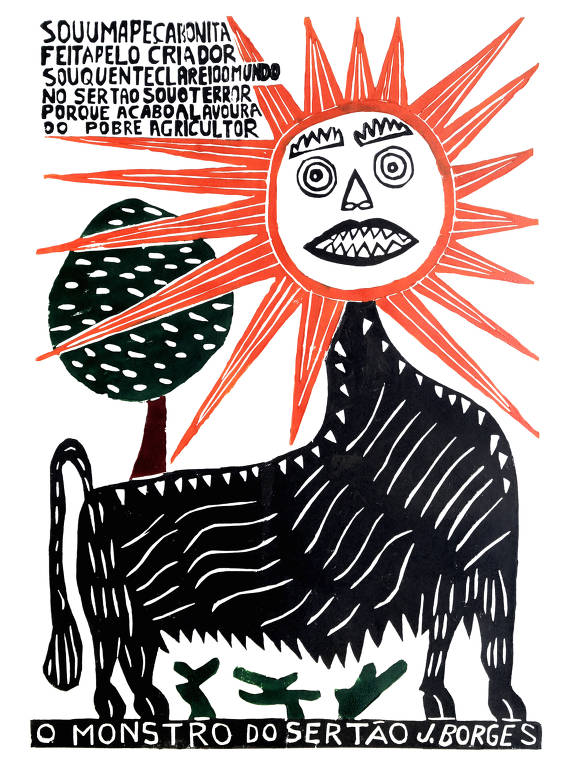

J. Borges, o maior xilogravurista brasileiro, poeta e cordelista, morreu em sua cidade natal, Bezerros, em Pernambuco, nesta sexta-feira, aos 88 anos. O Brasil se despede de um artista grandioso que encantou milhares de pessoas e que aprofundou a visão de todo o país sobre o Nordeste e a vida sertaneja —seus pássaros, sua beleza, suas cores e geografia, a perspicácia de seu povo, seus dramas e universo fantástico.

Tratou dos mais diversos temas: amor, morte, mistérios e fantasias. De fazer o povo rir, de safadezas, de falta de honestidade na política, dor de corno, profecias como fim de mundo, fim de século, fome, peste, guerras. Com Luiz Gonzaga, talvez tenha sido o mais importante narrador contemporâneo da realidade nordestina.

O artista construiu sua vida a partir de intensa observação do vivido e sem desviar da realidade, por mais brutal que fosse. Nascido na zona rural, viveu os dramas de muitas famílias, trabalhando desde criança na lavoura. Estudou apenas um ano, quando aprendeu a ler e escrever. Teve uma longa vida de trabalho, que só terminou com ele. Dias antes de sua morte, tinha iniciado uma xilogravura.

Desde a infância, tomou contato com a literatura de cordel. E, dali para a frente, mesmo com outras profissões —como pedreiro e marceneiro—, sua imaginação despertou para a magia trazida pelas narrativas. A paixão o levou a vender e a contar em voz alta nas férias de Bezerros e arredores, como era costume, as histórias de outros criadores, até que um dia começou a produzir as suas.

Animado pelas performances entusiasmadas dos escritores populares, pela encenação do que um dia chamou de "teatro do agreste e do sertão", fez do trabalho, de qualquer forma de trabalho, um desafio e uma alegria, tal qual os personagens de suas criações.

Completamente fascinado pelas aventuras, disputas e mistérios que estruturam as narrativas de cordel, encontrou nessa forma de literatura um forte paralelo com sua própria vida. Uma vida de lutas e desafios contínuos, onde a sobrevivência ocupa lugar central.

Se, por um lado, podemos ver sua intensa produção como resultado desse entendimento da vida como luta sem fim, por outro vemos que sua obra amplia os sentidos da ideia de luta, para além das contendas e dos conflitos.

Não que eles inexistam. Ao contrário, foram inspirações de muitas histórias. Mas Borges parece nunca ter desviado dos problemas, fazendo deles estímulo para o encontro de soluções. Sua primeira xilogravura, por exemplo, nasce da dificuldade em obter matrizes para as capas de suas histórias.

Seu mergulho nesse universo criativo nos faz refletir sobre como a inspiração pode estar relacionada, visceralmente, também à questão de sobrevivência: sempre foi um grande criador, cheio de imaginação e talento.

Mas a falta de dinheiro, a necessidade de alimentar os numerosos filhos —18 próprios e seis adotados—, os pedidos e desafios propostos pelos "clientes", o levaram a explorar qualquer tipo de assunto sem perder suas características próprias. A tudo encarou com energia inusitada.

Suas gravuras impressionaram Ariano Suassuna, que se tornou um grande divulgador de sua produção e o chamou de melhor gravador popular do Nordeste. Esse encontro foi fundamental na vida do artista, pois despertou o interesse nacional e internacional por sua obra.

Viajou para mais de 15 países, fez exposições e deu aulas. Em 2000, expôs no Louvre, em Paris, e em 2002, foi destaque no New York Times. Com Eduardo Galeano trabalhou por quase dois anos, quando ilustrou um livro, a partir das narrativas do escritor uruguaio.

Ilustrou um conto de José Saramago. Sua gravura da Sagrada Família foi presenteada pelo presidente Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva ao papa Francisco, em 2023. E, em 29 de junho, inaugurou no Museu do Pontal sua mais extensa retrospectiva, com 200 obras, contando um pouco da sua trajetória de 60 anos de produção artística.

Recebia os estudantes e os turistas em seu ateliê, falando sobre a importância de buscar a felicidade, e, com isso, não era piegas. Apenas queria transmitir sua experiência de homem pleno, cujo trabalho deu sentido à própria vida. Refletiu lindamente sobre a arte: "O sentido do artista é a criação. Gosto muito da liberdade de trabalhar criando o que me satisfaz. A arte dá liberdade ao pensamento humano, alimenta o espírito."

Tomar contato com a produção de J. Borges é entrar na dimensão fantástica da imaginação, com toda sua complexidade e singeleza. Borges apresenta o seu mundo vivido, experimentado, observado. Sua obra pautou o imaginário brasileiro sobre xilogravura.

Quando pensamos sobre essa arte milenar, nos vêm à mente as criações de J. Borges. Esse Sol do sertão, que nunca se apagará.

FOLHA

:extract_focal()/https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.newyorker.com%2Fphotos%2F66a140d781fa174be41eed93%2Fmaster%2Fw_1600%252Cc_limit%2Fr44634.jpg)

:extract_focal()/https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.newyorker.com%2Fphotos%2F66a140d76e5886fa16456cf3%2Fmaster%2Fw_1600%252Cc_limit%2Fr44635.jpg)

:extract_focal()/https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.newyorker.com%2Fphotos%2F66a140d74bbdf6f494bb6e5f%2Fmaster%2Fw_1600%252Cc_limit%2Fr44636.jpg)

:extract_focal()/https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.newyorker.com%2Fphotos%2F66a140d70685e1ca3174e6a4%2Fmaster%2Fw_1600%252Cc_limit%2Fr44637.jpg)

:extract_focal()/https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.newyorker.com%2Fphotos%2F66a140d94716f4448d88482e%2Fmaster%2Fw_1600%252Cc_limit%2Fr44638.jpg)

:extract_focal()/https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.newyorker.com%2Fphotos%2F66a140d84bbdf6f494bb6e61%2Fmaster%2Fw_1600%252Cc_limit%2Fr44639.jpg)

:extract_focal()/https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.newyorker.com%2Fphotos%2F66a140d948987bd585dbd071%2Fmaster%2Fw_1600%252Cc_limit%2Fr44640.jpg)