His wife, Martine Gossieaux Sempé, announced the death to Agence France-Presse. His biographer, Marc Lecarpentier, said Sempé — as he signed his work and was known universally — died at a vacation home, but did not specify where that was, AFP reported. Sempé had a home and studio in Paris.

In a nighttime panorama of sleeping city skyscrapers, Sempé illuminated a ballerina in a window. On the soaring span of the Brooklyn Bridge, a lone Sempé bicycle rider churned bravely. And before a large blackboard choked with Einstein calculations, his scruffy little genius soft-boiled an egg

It was timeless storytelling without words, a kind of pictorial haiku, the droll whimsies of an illustrator who never attended art school but who, for a half-century at the drawing board, had bypassed life’s meanspirited realities for a mythical world of mischievous schoolboys, daydreamers, nosy neighbors, holidaymakers and swooning lovers.

And in a collaboration with the writer René Goscinny begun in 1959, he illustrated a series of children’s books based on the escapades of Le Petit Nicolas (Little Nicholas), a nostalgic version of postwar French childhood. Their first volume was an overnight success, then came four sequels, and in time the series became an international classic, reprinted in France, the United States and many other countries.

Sempé, who also composed graphic children’s novels, eventually produced or collaborated on more than 30 books, which were translated into 37 languages and sold millions of copies worldwide.

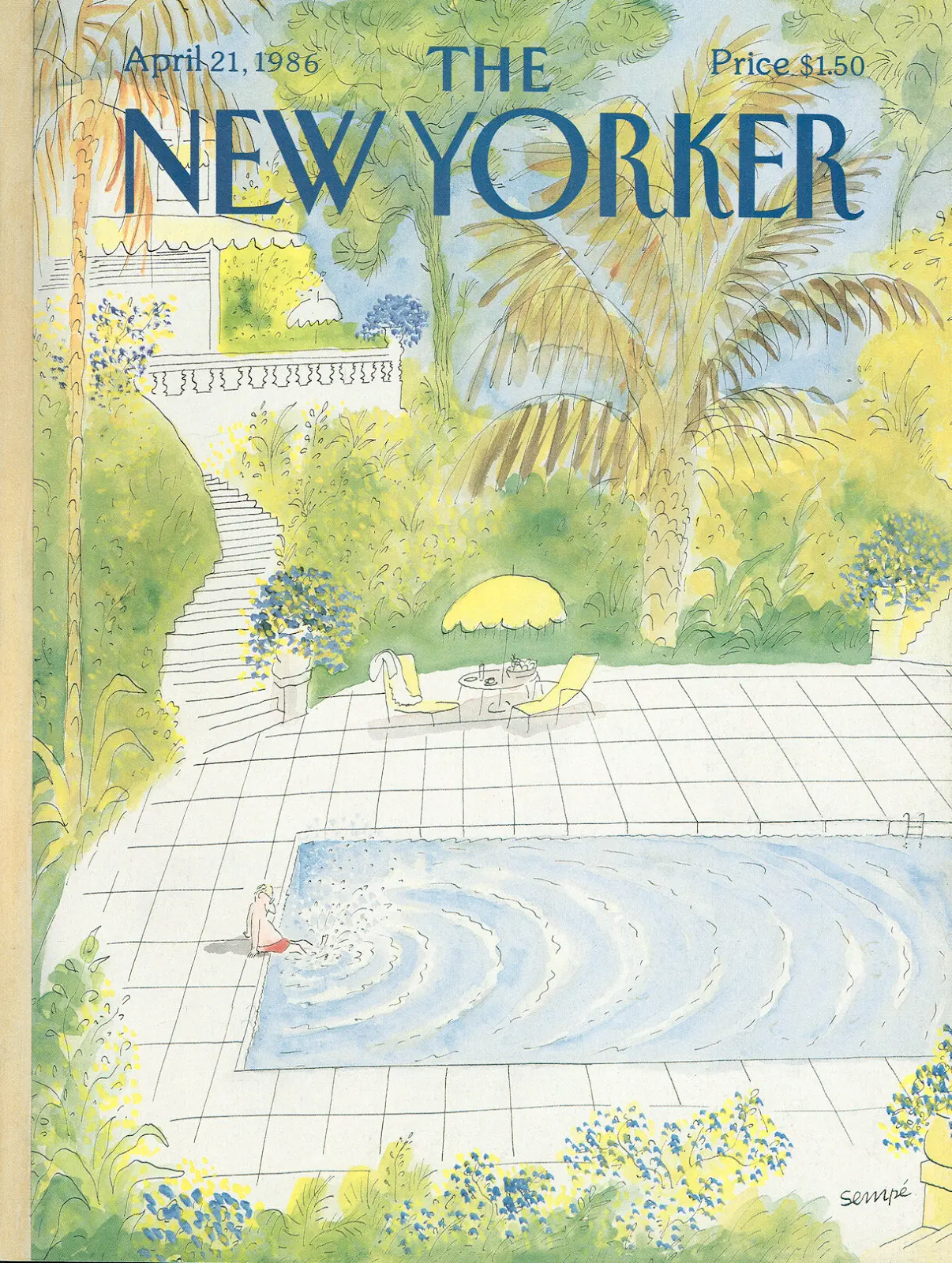

Ruddy and white-haired, he lived and worked in Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris, but he often traveled to New York to confer with editors and publishers and to collect ideas for his spidery pen-and-ink drawings, which made generous use of vivid watercolors or white space. His long and wide perspectives took in sweeps of sea and sky, great forests or monumental rooms that dwarfed the small dramas that were his focus.

His subjects were office workers, housewives, delicate little girls, frustrated commuters, pretentious intellectuals, musicians, roller skaters and bike riders, whom he adored because he was one of them. His men were likely to be portly and balding, with tidy mustaches and sometimes wearing berets; the women were often double-chinned matrons in polka-dot frocks.

“He’s a national institution who has acquired an almost universal appeal by remaining quintessentially French,” Charles McGrath wrote in The New York Times in 2006. “His precise, elegant drawings are often set in a Paris that even Parisians dream of: a city of mansard roofs, high windows and wrought-iron balconies, where all the cars still look like Deux Chevaux or 1950s Citroëns.”

Each New Yorker cover was like a scene from a larger story, and Sempé’s enormous backdrops exaggerated the effect. On Oct. 24, 2005, it was a tiny dancer in a tutu, waiting to be called while sitting on a bench under the statue of a great ballerina in a gigantic performing space. On Nov. 14, 2011, it was a small boy with a violin case, looking in at a studio of towering basses, huge drums and a menacing maestro pounding a grand piano.

On the gentler side were the Sempé cats. One luxuriated on a fluffy bedspread by a picture window overlooking Manhattan; another perched on a banister newel post, master of his empty household. One multi-panel Sempé cartoon showed a single autumn leaf spiraling to the ground from a tree, and a hand throwing it over into another yard.

He offered touches of modernity — a cellphone or a computer — but bicycles and roller skates more often kept his drawings stubbornly in a retro age, and the worlds of classical music and the performing arts lent timelessness to his work. Any concertgoer could recognize the symptoms.

Spoofing orchestral performers’ habitual use of the arm wave to deflect credit to others onstage as an appreciative audience roars, Sempé portrayed an entire orchestra in a daisy chain of arm-waving that began with the conductor and pianist, wound back through the ranks of strings and horns, and finally ended far in the rear, where a small percussionist beamed and bowed.

With the caption “C’est La Vie!” he drew four couples in separate boats on a fishing vacation — the men in the bows facing the points of the compass with their lines out; the women gossiping in the sterns, which were lashed together.

To illustrate the pride of the French housewife dedicated to cleanliness, Sempé drew madame polishing the tracks of a railroad line that ran just outside her front gate.

For sheer joy, he drew a girl skipping rope on a tenement roof with the great city rising behind her like an audience of the future.

And for sheer glad-to-be-alive happiness, there was Sempé’s man in the dunes, alone at the beachfront at the end of a perfect September day, tipping his hat at the incoming Atlantic.

“Vulnerability is la condition humaine, and my vulnerability is reflected in that of the people I draw,” Sempé told The Times in 1980. “You must see inside the people you draw to be a good artist — or a good humorist.”

Jean-Jacques Sempé was born in Pessac, a suburb of Bordeaux, on Aug. 17, 1932, to Ulysse Sempé and Juliette Marsan. As a boy he liked to doodle, but he was an indifferent student and was expelled from school for being undisciplined. He took exams for jobs at the post office, a bank and a railroad, but failed them all. He sold tooth powder door to door and delivered wine for a time.

At 17, in desperation, he lied about his age and joined the French Army.

“That was the only place that would give me a job and a bed,” he told The Times.

CAUGHT doodling on guard duty and reprimanded, he was sent to the stockade when his age was discovered. Discharged, he moved to Paris, where he won an award for young artists in 1952. He began selling illustrations to the magazines Paris Match and L’Express and the comic book Le Moustique, in which he drew a schoolboy called Nicolas. Mr. Goscinny suggested collaborating on a book, and the result was “Le Petit Nicolas,” told from the boy’s vantage. Sequels were produced. An American edition appeared in 1962, and many volumes were published over the succeeding decades.

Sempé was married three times and divorced twice. His first wife was the painter Christina Courtois. He and his second wife, the artist-illustrator Mette Ivers, had a daughter, Inga Sempé, born in 1968. Since 2017, he had been married to Martine Gossieaux, a gallery owner who had also been his agent. Complete information on survivors was not immediately available.

The cartoons of Charles Addams, Saul Steinberg and James Thurber inspired Sempé to draw for The New Yorker. Anthologies of his cartoons include “Nothing Is Simple” (1962), “Everything Is Complicated” (1963), “Sunny Spells” (1999) and “Mixed Messages” (2003). He also wrote graphic novels: “Monsieur Lambert” (1965), about friends in a bistro; “Martin Pebble” (1969), about a boy who blushes; and “The Musicians” (1980), with whimsical glimpses of the music world.

Sempé found his métier in the past. “I love to draw street scenes, and that means that you have to draw cars, but I hate drawing modern cars,” he told the British newspaper The Independent in 2006. “They are very fast and very efficient, but they have no charm. “For me, he added, “the modern world lacks charm. I am not saying that things were always better in the past. They weren’t. But things looked better, or at least more interesting, to me.”

No comments:

Post a Comment